A Fast-Emptying Ark

The World Grows Quieter by the Day

I confess, for reasons I can’t fully explain, that when bad things are happening to animals I tend to look away in pain. When bad things are happening to people I try to face those things squarely and do what I can, but there’s something about wildlife—perhaps the way its become implicated in our strange human game without having the slightest agency at all—that just confounds me; some kind of sad and disabling rage fills me. Sometimes, however, the truths are just too overwhelming to avoid.

A vast new study finds there are 70 percent fewer wild animals sharing the earth with us than there were in 1970. Read that again. And again.

To be more specific, the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Index, which monitors 32,000 separate populations of species around the world, found that on average they were 69% smaller than they had been in 1970.

This is not because we had an overpopulation of bears and monkeys and parrotfish in 1970—I was alive then, and I’m pretty confident in my memory that we weren’t overrun with wildlife. Instead it’s because we haven’t reined ourselves in, in any way—it’s because we (with a particular emphasis on those with the most money and power) have claimed ever more of the planet for ourselves, often without really knowing it.

The WWF says “these populations, or trends in relative abundance, are important

because they give a snapshot of changes in an ecosystem. Essentially, declines in abundance are early warning indicators of overall ecosystem health.” Fair enough—it clearly bodes ill for all of us that our waterways and forests can no longer support as many animals as once they could.

But that’s not what makes me so desperately sad. It’s that so many trillions of animals are dead, gone. The world is so much lonelier than it’s ever been before, at least in the long eons since fish started crawling out on land. The wondrous, comical, cruel, buzzing, gaudy, sexy carnival that is Life has shut down most of its tents; the symphony of grunts, squeaks, roars, belches and barks has faded to a diminuendo chorus. The creatures that always informed human dreams—that ended up on masks and totem poles, daubed on the walls of caves—have wandered away into the mist.

Over those five decades most of the decline can be traced to habitat destruction: the human desire for ever more stuff playing out daily, acre by acre, across the globe. I want a hamburger; a Brazilian entrepreneur wants money; together we hire (by the magic of ‘the market’) some poor soul who wants only to feed his family, and he cuts down another swath of rainforest, and with it a dozen species we haven’t even named yet. I want a house to live in and the wood must come from somewhere, and the coal and the oil to power it, and to power the car that takes me from there to the store; one of the ironies of the report is that wildlife has declined least in North America and Europe, in part because it had declined pretty steeply there prior to 1970, and in part because we’ve been rich enough to preserve some of our landscape. Rich enough because we’ve had access to so many other landscapes.

But in the decades ahead the report makes clear that climate change will be the main driver of what they call, in a technically precise but emotionally vacant phrase, “biodiversity loss.” As we raise the temperature (and the pH) of the oceans, we destroy those reefs that harbor so much of its beauty; as we raise the temperature of the air we drive animals up the mountain till they hit the summit, and north till they run out of north. As Benjamin von Brackel writes in his moving new book Nowhere Left to Go, “The closer they get to the Pole, the more the inhabitable territory shrinks. Earth is an ellipsoid, after all.”

If you want good news, it’s that populations can in fact recover—reproduction is a powerful force, and given some space, animals can rebound. (The authors of the new report note that when a couple of small and no-longer-useful dams were torn down on some New England streams, herring populations quickly rebounded from a few thousand to a few million, which doubtless did wonders for whoever eats herring too). There are paradoxes here: building out clean energy is going to take some land that’s useful for animals (see desert tortoises in the Mojave) but the scale of the destruction clearly in the offing if we don’t build out that energy means we should give the benefit of the doubt to sun and wind; still, learning to do it in ways that offer the fewest insults to the rest of creation is what we should aim for. Fill solar farms with native plants for bees and butterflies. Build them with wildlife corridors Use offshore turbines to build coral reefs. But above all don’t let the planet keep warming.

The WWF report points out that we can’t achieve the world’s Sustainable Development Goals (or SDGs) unless we prevent a climate-led biodiversity collapse. That’s true, and that’s crucial. And we also can’t have a whimsical, magical, various world. Today, as I write this, the fall color in Vermont has reached its apex for the year; the forest is fantastically decorated. I can hear, as I walk the dog in the evening, the hoot of the barred owl. A deer just sauntered by. It’s too much, and (compared with all prior history) not nearly enough.

In other climate and energy news:

+A big new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis makes it clear that divestment from fossil fuel remains the smartest financial strategy, even on a year when Putin has driven the price of oil sky high

Competitive forces inside and outside the industry have undermined this once-mighty economic force. Politics now drives oil and gas prices, with the war in Ukraine serving as a vivid reminder of this stark reality.Market forces now favor fossil fuel competitors; cost efficiencies, innovation and public opinion are converging to move trillions of dollars to sustainable alternatives. Meanwhile, an increasing number of destructive weather events have underscored the destruction caused by climate change and increased public demands for solutions.

Investors should move away from fossil fuels because the coal, oil and gas sectors are confronted with competitive pressures that they are ill-prepared to navigate.

+People with disabilities—about a billion humans—are particularly vulnerable to the dangers of climate change, a new report finds. And they’re not consulted about any of it.

The researchers found that only 32 of the 192 countries that are signatories to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Paris climate accords in 2015 refer to people with disabilities in their official climate plans. Forty-five countries refer to disabled people in their climate adaptation policies and no country mentions disabled people in its climate mitigation plans. Many of the world’s biggest contributors to climate change – the United States, China, Russia, Brazil, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom – don’t figure people with disabilities into any of these plans, according to the report.

In the same vein, new data from around Europe makes clear that older people are far more vulnerable to heat waves

At the peak of its heat wave, England recorded 2,803 excess deaths among those 65 and older, according to a recent analysis by the U.K. Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and the Office for National Statistics. The government agencies said that was the highest figure among the elderly since they started tracking heat-related deaths in this way in 2004. “These figures demonstrate the possible impact that hot weather can have on the elderly and how quickly such temperatures can lead to adverse health effects in at-risk groups,” the groups said in a statement.

+Putin’s war seems to be speeding up the pace of Europe’s conversion to renewable energy, according to new data from Politico

But the next couple of years won't be easy. The invasion caught the EU mid-straddle in its energy transformation. A lot of the groundwork for a greener future is in place, but capacity in everything from training workers to insulate buildings and install wind towers, to cutting red tape for wind and solar permitting, redesigning grids to handle renewables and ramping up hydrogen production, is still a work in progress.

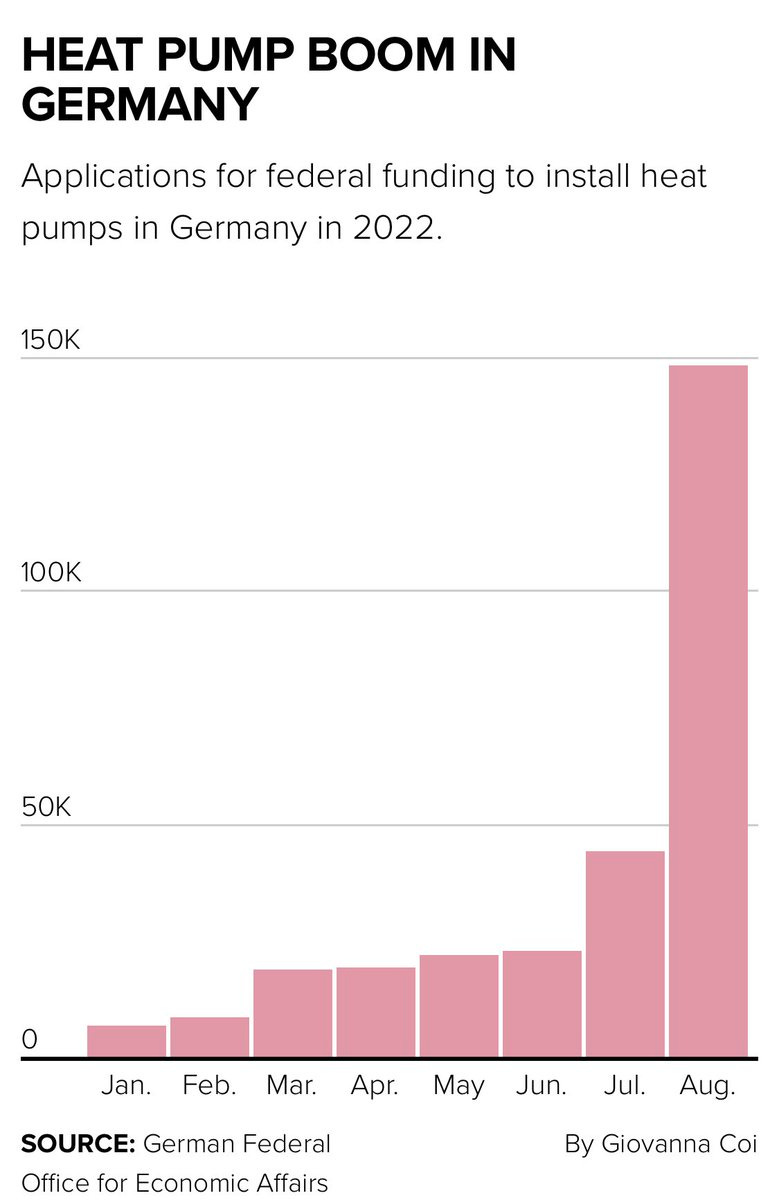

For readers of this newsletter, the data on heat pumps is especially gratifying. Here’s what’s happening in Germany:

+Great reporting from Nina Lakhani in the Guardian about how Big Oil tries to buy support in the Black community by bankrolling politicians. So many nasty old names in play, including TC Energy, the company that tried to bring you the Keystone XL pipeline

TC Energy’s affiliates have spent $4.3m on lobbying in this election cycle, in addition to $200,000 in campaign contributions, according to federal campaign disclosures tracked by Open Secrets.

+Season 3 of the Matter of Degrees podcast is up and running! Hooray

+The good people at Good Energy have released a compelling new study of how much (actually how little) attention Hollywood pays to climate change: as the indefatigable Anna Jane Joyner points out, only 2.8% of scripts pay even passing attention to the greatest crisis of all time. (And thanks to unceasing campaigner Norman Lear, whose eponymous USC center helped with the report)

“I think what really surprised me is the fact that audiences believe that they care about climate change more than the characters on TV [and in film] do,” Joyner says. “And it was also striking to me that when climate disasters show up in television and film — droughts, heat waves, wildfires, monster hurricanes — they’re only connected to climate change in a script 10 percent of the time. When the fossil fuel industry comes up in a script, it’s only connected back to climate change like 12 percent of the time. Those are two areas where it feels like scripts should be making more of that connection when they come up.”

Thank you, Bill. This sensitivity to the larger crisis (our rapid impoverishment of the community of life) should be an essential part of the daily climate conversation. It's easy to forget that for all its terrifying power, the climate crisis is just one symptom of the deeper illness. I'm not sure whether we are, metaphorically, a slow-moving asteroid or a fast-moving supervolcano, but as the new numbers from the Living Planet Index make clear the impact on species and their ecological communities is approaching the literal definition of "decimate": to reduce by 90%. It's not a mass extinction, but it certainly feels like the event horizon of one.

It's easy to feel buffered from the losses - whether wasps, alewives, hemlocks, wolves, or painted turtles - when we live our boxed-in lives. It's even easier here in coastal Maine, for example, when eight species of birds flurry at the feeder at dusk before the rain and winds set in, when a posse of turkeys forage in the squash patch, and when the second-growth forest echoes with barred owls and coyotes. We have to pay attention to see how much has changed (like the coyotes, at least two of the feeder species, cardinals and titmice, didn't exist here 50 years ago), how much is missing, and how quickly what remains is being lost at home and elsewhere (particularly those distant communities we've hijacked).

As you note, any climate solution that isn't also a biodiversity solution is a lost opportunity at a time when we can't afford lost opportunities. It kills me to see new solar farms being built on the stubble of a former forest - there's good seed money in a clearcut, I guess - when open land is available nearby.

So again, thank you for sharing your grief and connecting the dots between climate and biodiversity. Your writing is beautiful and important, as always.

If we expand our framing, from carbon emissions driving climate change, to energy extraction from hydrocarbons diminishing habitats on earth that are inhabitable by humans, the link to biodiversity loss becomes, I think, a bit more logical, and maybe obvious.

Keith Johnson gives us a nice Midwestern phrase for the world we are living in today: "We are eating our seed corn."

Great fortunes for individuals are being extracted from a future that is diminshing for all of us.

The culprit?

The Growth Imperative of share price trading.

Would we ever be able to imagine a different way of providing financing to enterprises operating at scale, that is not reductionist, extractive, externalizing and uncaring about the future?

Here's a clue. The word "fiduciary" is legal for caring. Could we imagine the innovation of a new system of fiduciary financing for fiduciary-grade enterprise that is design to care?