A Pashtun Muslim Leader Might Have Been the Noblest Man of the 20th Century

We've left Afghanistan--but that doesn't mean we can't learn a great deal from its (nonviolent) history

We’ve been “out of Afghanistan” for a week now, so it’s entirely possible Americans will forget about the region for a while. I hope not, and not just because of the people whose lives hang in the balance. But also because it’s possible that the most interesting man of the twentieth century was a Pathan Muslim tribesman from the mountains of Afghanistan—he’s one of my great heroes anyway, and I’ve been thinking about him a lot in recent weeks, convinced as ever that his story could teach us powerful lessons. If you take a moment out of your day to read his story, I think you’ll find it worth the time.

One thesis of this newsletter is that nonviolent movement building is a uniquely important way to challenge entrenched economic and political power. And perhaps its greatest early practitioner was Abdul Ghaffar Khan. He was born in 1890 along the banks of a tributary to the Swat River, near the city of Utmanzai, which is now on the Pakistani side of the border with Afghanistan, but then was part of the vast sweep of British India. The Khyber Pass, the Hindu Kush—this was the land of the Great Game, remote and isolated but strategically crucial to the Empire. Khan was educated in a missionary school, where he excelled; offered a prestigious commission to the imperial army he turned it down, and at the age of 20 opened a madrasa in the nearest town. The British (who locked in the stocks any Pathan who didn’t bow low enough when they approached) decided it was subversive and soon closed it down; instead of taking up arms, Khan decided in turn on a path of social reform. He wandered the entire district, visiting all 500 villages, opening up old schools, and trying to talk village elders out of the cycle of vendetta and honor killing that marred local life; he was successful enough that he was soon known as Badshan Khan, or Khan of Khans.

His biographer Eknath Easwaran says that at some point in these excursions, meditating in a closed schoolhouse, he had a conversion experience not unlike Saint Francis’s. “Islam! Inside him the word began to explode with meaning. Islam! Submit! Surrender to the Lord and know his strength.” But it didn’t turn him into a religious zealot—quite the contrary, he was long an advocate for a secular India, and by 1929 he had met the man who would be his greatest colleague, Mahatma Gandhi. They were a contrast in every way—if Gandhi was tiny and frail, Khan was a lion of a man, 6 foot 3 and immensely strong. He understood “jihad” to mean struggle against one’s own weaknesses and temptations, and in his community that often meant the resort to violence—so, in a brilliant flash of inspiration, he formed an army, called the Khudai Khitmatgar, that wore a distinctive red shirt and took the most unusual of military oaths:

I promise to refrain from violence

I promise to forgive those who oppress me or treat me cruelly

Women joined as well as men; all volunteers, they gave at least two hours a day to community work, often building schools. But their oath would soon be tested. When Gandhi launched his Salt March in 1930, Khan joined him in nonviolent protest and was soon arrested. A crowd gathered in the Kissa Khani Bazaar in Peshawar to protest his arrest, as it was dispersing British armored cars arrived and drove in amongst the throng, killing several. As the protesters paused to gather their dead, the British opened fire. Gene Sharp, the pre-eminent historian of non-violent action, described the scene that followed:

“When those in front fell down wounded by the shots, those behind came forward with their chests bared and exposed themselves to the fire, so much so that some people got as many as twenty-one bullet wounds in their bodies, and all the people stood their ground without getting into a panic. This state of things continued from eleven o’clock until five in the evening. When the number of corpses became too many, the ambulance cars of the government took them away and burned them.”

Imagine, that is, a Kent State massacre that lasted not for 30 seconds but for the better part of a day—the number of dead may have reached 300, though no one really knows, since unlike most of Gandhi’s battles, this one was fought far from cameras and foreign journalists. It began a season of almost unimaginable barbarity, with the nonviolent volunteers killed en masse—“gunning for redshirts” became a pastime for British officers. But none of it broke the nonviolent spirit of the Khudai Khitmatgars. And their resolve sent a serious shudder through the Brits: whole companies of the crack local troops, like the Garwhal Rifles, began refusing orders to fire. (Several officers were sentenced to life in prison for insubordination).

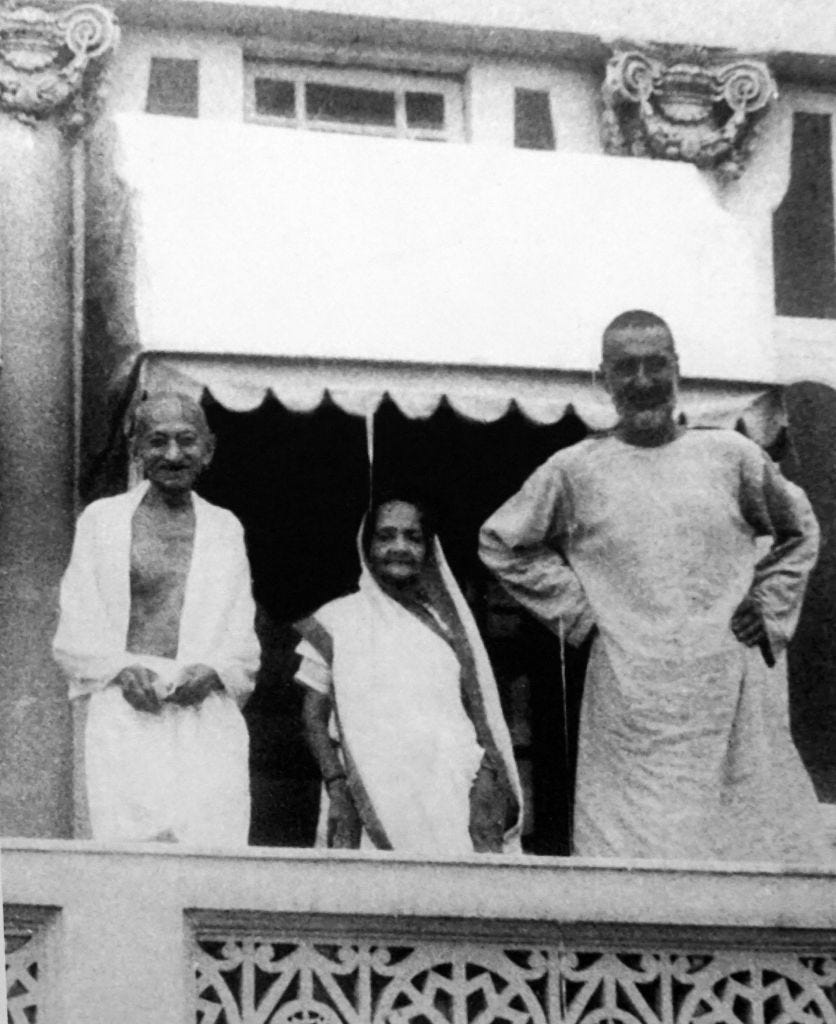

Across the sweep of the British Raj the uprising was successful—for the first time London had to enter into negotiations with independence activists. Limited self-rule was granted to the Frontier Provinces of the Pashtun, beginning the decade-long countdown to independence. When it came, of course, the British divided India and Pakistan, shattering Khan and Gandhi’s hopes of a multi-faith democracy. The two of them had wandered the country together, reading from each other’s scriptures in prayer’s meetings—there are moving images of Gandhi napping with his feet in Khan’s lap. Their failure—even as they’d won independence from the British—was crushing. Gandhi, of course, was soon killed by Hindu fanatics; Khan was soon back in jail, this time at the behest of the Pakistanis, who feared his call for Pashtun self-government.

Khan lived into the modern era—and though spent much of his life behind bars, his example remained powerful. He was adamant in defense of women’s rights and of nonviolence; his last (successful) campaign was against a dam that would have damaged a valley near Peshawar. When he died in 1988, under house arrest, tens of thousands people accompanied his body on a days-long trek across the Khyber Pass to Jalalabad—fighting halted for five days in the Afghan-Soviet war.

A reborn Khudai Khitmatgar in India has tried to press for Muslim-Hindu amity, but the fanatics who killed Gandhi have repressed its efforts; in Afghanistan and Pakistan, obviously, the hard men currently have the upper hand. But for me his story helps me avoid easy generalizations; that perhaps the greatest nonviolent practitioner of all time was a Muslim who led an army of 100,000 should cast some shade on prejudices it’s hard for us to shake.

I don’t know quite what lessons can be drawn from his life—surely one is that the deep wounds of imperialism and colonialism linger still. But they’re not impossible to overcome. Those young women students who escaped from the Taliban to places like Mexico and Rwanda seem his heirs. Many more of us need to take up that inheritance. The fights may not always be as dramatic. But at this point in the human story, our future may well depend on our ability to reach back into our shared heritage and rescue the examples of courage that will give us the heart to act beyond our comfort zone.

Bill, what wonderful and inspirational lessons about the power of civil disobedience and non violent movements!

Just don't adopt redshirts for us ... perhaps gray green patterned ones with a high SPF factor from Eddie Bauer.

We may not have money to compete head on with the Koch Family and the powerful Fossil Fuel industry and their PR machine ... but we can get 'experienced and caring volunteers'.

We should look at the 'volunteers' in this story just as we should prioritize in the ThirdAct by mobilizing and utilizing 'experienced and caring volunteers' to advance environmental justice in our global climate crisis.

There are many forms of justice and it is hoped, from a political perspective, that the ThirdAct can partner with other organizations in developing Voter Guides at all levels of government to examine candidates through the lens of environmental justice.

**BM Women joined as well as men; 'all volunteers', they gave at least two hours a day to community work, often building schools.

**BM It began a season of almost unimaginable barbarity, with the nonviolent 'volunteers' killed en masse—“gunning for redshirts” became a pastime for British officers. But none of it broke the nonviolent spirit of the Khudai Khitmatgars.

The call for us to have 'timely courage' is right on if we are to wane off the most serious of climate tipping points attributable to more and more extreme and costly weather events. You and many more experienced these with Ida in NYC and the Mid Atlantic.

Too little 'courage', or failing to get out of our physical and mental 'comfort zones', will equate to too much physical suffering for the global human community and nature as we know it today. Human migrations and the GeoArbitrage process seeking a Climate Haven are already beginning.

**BM But at this point in the human story, our future may well depend on our ability to reach back into our shared heritage and rescue the examples of 'courage' that will give us the heart to act beyond our 'comfort zone'.

Thank you for posting this. I learned something new and important