Friction is growing

We're reaching the point where the climate crisis slows the machine

The economy of the rich world is a massive, geological force—it plows onward with glacial power, pushing through obstacles like global pandemics; if it stalls, it’s usually only momentarily before it picks up speed again. Or perhaps to use a better, internal-combustion-era metaphor, it’s a speeding tractor-trailer on a downhill run, barely able to brake even if it wanted to.

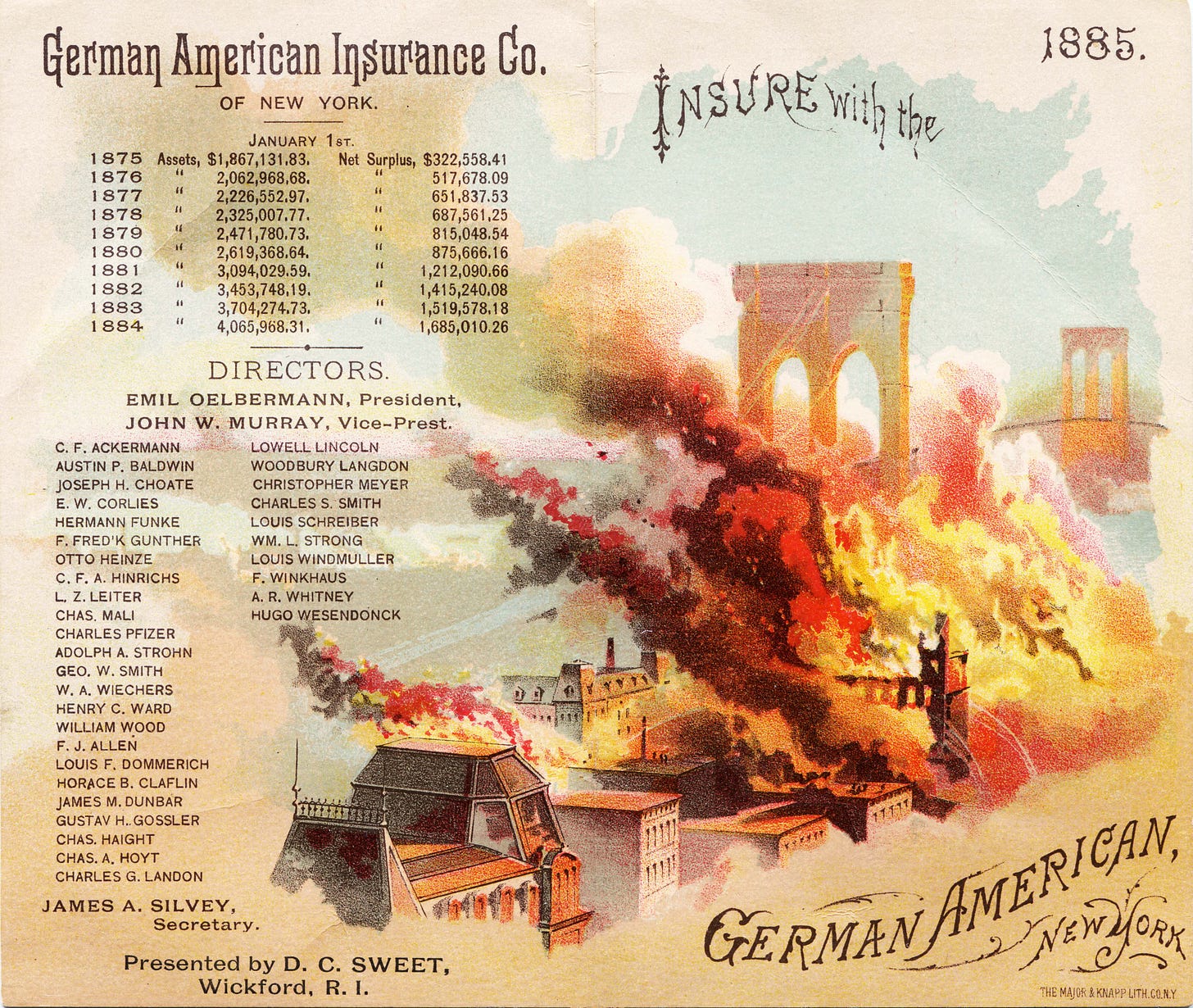

But I think we’re very near the point where—thanks to the climate crisis—the economy encounters sufficient friction to slow it, and maybe even to send it in a careening spin. Last week the Wall Street Journal (whose news columns are as useful as their editorial pages are obtuse) published a long piece of reporting with a stark headline: “Buying Home and Auto Insurance Is Becoming Impossible.”

The essay began by describing the way that Allstate—after suffering billions of dollars in losses last year—threatened to stop writing policies in New York, New Jersey, and California. Regulators in all three states, terrified of that possibility, let them raise rates by preposterous amounts

In December, New Jersey approved auto rate increases for Allstate averaging 17%, and New York, a 15% hike. Regulators in California are allowing Allstate to boost auto rates by 30%, but still haven’t decided on its request for a 40% increase in home-insurance rates after the insurer refused to write new policies.

The Journal was entirely clear about the reasons:

The past decade of global natural catastrophes has been the costliest ever. Warmer temperatures have made storms worse and contributed to droughts that have elevated wildfire risk. Too many new homes were built in areas at risk of fire.

And it was entirely clear about the likely consequences:

“Climate change will destabilize the global insurance industry,” research firm Forrester Research predicted in a fall report. Increasingly extreme weather will make it harder for insurance companies to model and predict exposures, accurately calculate reserves, offer coverage and pay claims, the report said. As a result, Forrester forecast, “more insurers will leave markets besides the high-stakes states like California, Florida, and Louisiana.”

Allstate CEO Wilson said: “There will be insurance deserts.”

Insurance deserts, where private-sector companies no longer will sell regular home-insurance policies, are already developing in high-risk areas. Florida’s insurer of last resort is now the main provider of home coverage in that state.

As I read all this, I flashed back to a 2005 study I’d written about at the time. Swiss Re, one of the world’s biggest reinsurance firms, had hired a team from Harvard to model the effects of increased climatic upeheaval. It found that as storms and other disruptions become more frequent, they “overwhelm the adaptive capacities of even developed nations; large areas and sectors become uninsurable; major investments collapse; and markets crash.” Pay careful attention, despite the bland phraseology:

In effect, parts of developed countries would experience developing nations conditions for prolonged periods as a result of natural catastrophes and increasing vulnerability due to the abbreviated return times of extreme events.

“Abbreviated return times of extreme events” is a bland enough phrase, sort of like “objects in mirror may be closer than they appear,” but it is a pretty good caption for our moment: here where I live in Vermont (which is sometimes thought of as a ‘cliamte refuge’), we’re dealing with floods and storms at a rapidly increasing rate—a spokemsan for our local utility said last fall that “our three worst storms were last year.”

Homeowners unable to get affordable insurance is a problem in and of itself, but what it really presages is what the Harvard team described: a drag on the economy that eventually causes real change. Insurance sounds like a boring topic, until you think about it a little: it’s the (enormous) part of the economy that’s assigned to understand risk. And to do so it developed one of the most powerful technologies in all of human history: the actuarial table. Using it, the industry can predict what’s going to happen—predict it accurately enough to allow everyone else to affordably hedge against that risk. Without that hedge, investment—in a house or a company—becomes almost impossible. Climate change is wrecking that tool, because an actuarial table depends for its power on the world behaving more or less as it has in the past. As the Journal put it, succintly, “climate change has made it harder for insurers to measure their risks, pushing some to demand even higher premiums to cushion against future losses.”

Don’t cry for insurance companies. Not only do they figure out how to charge higher premiums, they’ve also helped create this crisis: with the biggest pool of investment capital on the planet, they’ve continually helped fund the expansion of fossil fuels, and these same companies continue to underwrite the pipeline projects and LNG export terminals that are doing them in. (“When it comes time to hang the capitalists, they will vie with each other for the rope contract,” Vladimir Ilyich Lenin may or may not have said).

And perhaps we shouldn’t even cry for our own selves—insurance, after all, is a luxury available mainly to people in those places that have driven the climate crisis. Most of the world has been dealing with it without any help, a fact we were reminded of this week when a UN report delivered the staggering news that a quarter of our fellow humans—the vast majority in poor countries—were currently dealing with drought.

“Droughts operate in silence, often going unnoticed and failing to provoke an immediate public and political response,” wrote Ibrahim Thiaw, head of the United Nations agency that issued the estimates late last year, in his foreword to the report.

The many droughts around the world come at a time of record-high global temperatures and rising food-price inflation, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, involving two countries that are major producers of wheat, has thrown global food supply chains into turmoil, punishing the world’s poorest people.

I think even the powers that be are starting to recognize our peril—Sourcing Journal, (“the largest, most comprehensive and authoritative B2B resource for executives working in the apparel, textile, home and footwear industries”) warned last week that “extreme weather” was now the greatest threat to supply chains. (You read about attacks on ships in the Red Sea, but the big story in logistics right now is the drought that’s so lowered the water level in the Panama Canal that shippers have to send their cargoes on rail across the isthmus). And as the world’s leaders jet into Davos this week, the World Economic Forum has decided that even amidst AI and war, climate presents the greatest risk to our prosperity.

In the long term — defined as 10 years — extreme weather was described as the No. 1 threat, followed by four other environmental-related risks: critical change to Earth systems; biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse; and natural resource shortages.

(Note, by the way, that ‘long term’ is defined as the next decade, which should tell you something about how we got into this trouble in the first place).

To return to our metaphor, the enormous momentum of the global economy is beginning to run into the enormous friction of climate change. If we were all working with good faith to build systems that could absorb the shock, we’d have a chance. But at the moment the fossil fuel industry is—internal combustion metaphor again—pushing the pedal to the floor. Its response to the hottest year in the last 125,000? An eight-figure ad campaign launched last week “promoting the idea that fossil fuels are “vital” to global energy security.”

So on we fight.

In other energy and climate news:

+ The world added 50% more renewable energy in 2023 than in 2022, the International Energy Agency reports

The amount of renewable energy capacity added to energy systems around the world grew by 50% in 2023, reaching almost 510 gigawatts (GW), with solar PV accounting for three-quarters of additions worldwide, according to Renewables 2023, the latest edition of the IEA’s annual market report on the sector. The largest growth took place in China, which commissioned as much solar PV in 2023 as the entire world did in 2022, while China’s wind power additions rose by 66% year-on-year. The increases in renewable energy capacity in Europe, the United States and Brazil also hit all-time highs.

The latest analysis is the first comprehensive assessment of global renewable energy deployment trends since the conclusion of the COP28 conference in Dubai in December. The report shows that under existing policies and market conditions, global renewable power capacity is now expected to grow to 7 300 GW over the 2023-28 period covered by the forecast. Solar PV and wind account for 95% of the expansion, with renewables overtaking coal to become the largest source of global electricity generation by early 2025. But despite the unprecedented growth over the past 12 months, the world needs to go further to triple capacity by 2030, which countries agreed to do at COP28.

+My old friend Jacqui Patterson first documented this on behalf of the NAACP years ago, but apparently it’s a truly widespread practice: power companies across the South paying off “civil rights leaders” to shill against renewable energy. As the Guardian reports:

More than two dozen Black civil rights leaders in the south-east have been high-value targets in power companies’ battle for market dominance, courted and at times even co-opted by the industry, according to an investigation by Floodlight and Capital B.

The multibillion-dollar power companies use Black support to divert attention from the environmental harms that spew from their fossil fuel plants, the investigation found, harms which disproportionately fall on Black communities. One civil rights leader received power company cash as he built support for its attempted takeover of a smaller municipal utility in Florida. Another fought state oversight in Alabama that could have lowered electric bills and federal oversight that could have restricted emissions and pollution from coal-burning power plants.

Some civil rights and faith leaders “will sell you out because they’ll sell anything – they’ll sell seawater,” said the Rev Michael Malcom, executive director of the environmental justice organization Alabama Interfaith Power & Light, in Birmingham.

+The indefatigable Jane Fonda takes to the pages of Time to remind the health care industry that it needs to clean up its climate act

Our health care system is responsible for almost 9% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions because of the system’s reliance on fossil fuels to run its facilities and equipment, the petrochemical plastics used to make its devices, the anesthetic gases they use in the operating room, and the food and drugs it purchases.

Gary Cohen, co-founder of Health Care Without Harm, made me hopeful when he told me that the health care community—led usually by its nurses—has made big changes before. When they learned that medical waste incinerators were a leading contributor of cancer-causing dioxin emissions in the U.S., thousands of incinerators were closed and hospitals learned how to reduce their waste, reuse and recycle what they could, and use safer waste-treatment technologies to dispose of potentially toxic materials. When studies began to show that broken mercury thermometers were contributing to dangerous mercury levels in water and fish, the health sector phased out mercury thermometers and found safer alternatives, not only in our country but all around the world.

Health Care Without Harm has pushed hospitals and health care centers to commit to plans to achieve net zero emissions in the near future, and thousands more around the world are on the same path. More than 75 governments have committed to design low-carbon and climate-resilient health systems, including the U.S.

+San Diego just became the first Roman Catholic diocese in the U.S. to divest from fossil fuel! The National Catholic Reporter has the story:

The pivot in investment policy away from fossil fuels was done "in keeping with the Holy Father's ideas about stewardship of the environment and not wasting resources," along with addressing human-driven climate change, said Kevin Eckery, diocesan communications director.

"This wasn't what we wanted to be invested in and we had other things that we wanted to do," he said.

+A new paper documents that oil and gas drilling does far more damage to bird populations than wind turbines. Don’t tell Donald Trump, but an ingenious and data heavy report from Erik Katovich combines

longitudinal micro-data from the National Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count with geolocated registries of all wind turbines and shale wells constructed in the contiguous US during this period to estimate the causal effects of these contrasting types of energy infrastructure on bird populations and biodiversity – key bellwethers of ecosystem health. Results show that the onset of shale oil and gas production reduces subsequent bird population counts by 15%, even after adjusting for location and year fixed effects, weather, counting effort, and anthropic land-use changes. Wind turbines do not have any measurable impact on bird counts.

+The World Council of Churches is calling for a new legal framework to try and reduce climate misinformation.

"Without urgent intervention in relation to the spread of disinformation, lobbyists are likely to continue to undermine political will for the necessary action, emissions are likely to continue to increase, and the effects of climate change are likely to accelerate with catastrophic effects for people and the planet,” reads the text.

Rev. Dr Kenneth Mtata, WCC programme director for Public Witness and Diakonia, explained: “Many decision makers who are still financing or promoting fossil fuel extraction today, despite its consequences on children and future generations, are encouraged and enabled to do so by climate disinformation.”

+Teachers across the country are continuing to push to rid their retirement portfolios of fossil fuel investments. An excellent article by Don Nonini, Sheldon Pollock, and Dan Segal in Academe magazine concludes

The three largest private managers of faculty retirement accounts are Vanguard, Fidelity, and TIAA. According to multiple sources (IEEFA, Urgewald, Stand.Earth, Stop the Money Pipeline, Vanguard S0S, Action Center on Race and the Economy and TIAA-Divest), these financial firms are among the top fossil fuel investors in the world: Vanguard with $460 billion in fossil fuels; Fidelity with $162 billion, and TIAA with $78 billion—an astounding $700 billion in total. (Vanguard is in fact the largest carbon investor on the planet.) The total fossil fuel investments in public pension funds, which many public institutions provide faculty, are harder to calculate but may amount to something on the order of $150 billion.

Why should it concern faculty that their retirement monies are invested in fossil fuels? Precisely because these investments pose profound ethical, existential, financial, and legal risks, due to the unfolding climate crises caused by the carbon emissions of fossil-fuel-powered energy. Here we spell these out only in brief.

There is no retirement on a dead planet, and no liveable future for our students, whose futures our teaching aims to secure. Our students are, in fact, increasingly depressed and pessimistic due to the failure of the professional-managerial classes and political leaders of the last four decades to do anything remotely adequate to address climate change. We as their faculty have a moral obligation to do whatever we can to alleviate their present suffering and prevent the much greater catastrophes predicted over the course of their lives.

The system will keep bending, and bending, until it breaks. Where that will happen is anyone's guess. The insurance industry collapsing. Mass migration of climate refugees. Global shipping choked off by drought-plagued canals. War over scarce water supplies. Likely more than one breaking point. And all will wonder, why didn't we do more while we still could?

Excellent article. The insurance industry in North Carolina is requesting a 40% increase in home insurance costs! Eventually this will cause low income and those dependent on fixed income to sell their homes. As the climate crisis worsens, the value of homes will begin to collapse.