Film lodges images in your mind like no other medium. I was amazed this week—after scientists came up with startling new evidence that the great currents of the Atlantic are moving towards a shutdown—to find out how much of 2004’s The Day After Tomorrow I could still recall, especially the scene of the Statue of Liberty engulfed in a giant wave. The slowing of the Gulf Stream won’t actually flood the Lady in the Harbor, but the probable real-life results of slowing these currents would be far worse. As the Washington Post explained: “the dramatic cooling in the Northern Hemisphere would cause a shift in the band of clouds and rainfall that encircle the globe at the tropics. The monsoons that typically deliver rain to West Africa and South Asia would become unreliable, and huge swaths of Europe and Russia would plunge into drought. As much as half of the world’s viable area for growing corn and wheat could dry out.”

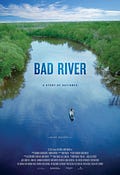

Bad River—a new documentary premiering in early March—is entirely unambiguous fact, not dramatized at all; if anything, some of its power comes from underplaying the tragedy it describes, that of an indigenous community forced to defend its remaining chunk of land from a heedless and rapacious oil company. But I’m pretty sure it’s going to stick in my head in somewhat the same fashion as that climate thriller, because the story is so universal and so particular all at once. You can watch the trailer here, and also find out about where to watch the whole thing when it opens at theaters March 15.

I’ve been emailing back and forth in recent weeks with Mary Mazzio, who made the film. She’s remarkable herself, having made a series of documentaries that spurred legislation and lawsuits that actually fixed some of the problems she identified. Her first film, “A Hero for Daisy,” tells the story of the early days of Title IX through the eyes of a Princeton rower.

“Back when it came out, a girls’ high school basketball coach from Tuba City, Arizona called me. “I’m Mac Hall and I’m calling from the Navajo Reservation. None of my girls are getting recruited by Division 1 programs,” he began. “So many of these college coaches have deeply ingrained stereotypical assumptions about Native girls,” he continued, explaining that a film project might help to dispel some of those biases.

I had only made one film back then and could not find funding for that project. But Mac Hall and his voice have been in my head for years. He really is the reason for this new project.

Fast forward to a chance introduction to Mike Wiggins, the Chairman of the Bad River Band. The Band had filed a lawsuit against a Canadian pipeline operator, and, as a recovering lawyer, I thought it incredible that this small community could mount such a David-and-Goliath battle.

The David and Goliath battle is between the Bad River band of Lake Superior Chippewa and Enbridge, the giant pipeline company who you may remember from other battles, like Line 3, rammed across the Mississippi headwaters, and the Dakota Access pipeline. In this case, it’s Line 5 at issue, carrying tarsands from Canada across the Great Lakes region, and then back into Canada. When I say “across the Great Lakes region,” I mean underneath the Straits of Mackinac, where Lake Michigan meets Lake Huron—I remember well coming to talk at an early protest against the pipeline more than a decade ago, and simply being stunned that anyone could ever have built such a thing, smack in the middle of the world’s largest supply of freshwater.

The pipeline also winds across the Bad River reservation—which, as the film makes powerfully clear, is the result of the entirely typical centuries-long mistreatment of Native Americans. But after every effort to reduce their power and their culture, the tribe still holds title to their relatively small piece of paradise (captured mostly via drone shots, which have opened up new possibilities for rural filmmaking), and it’s that legal title that helps drive the story. The band sued Enbridge in federal court in 2019, arguing that there was a profound risk of a catastrophic rupture that could send oil pouring into the waters around the reservation.

This is not some idle threat: the most shocking footage in the film shows that as the river has shifted the soil around the pipeline has eroded so much that in places the pipeline is just hanging there, completely exposed; it’s as grotesque and scary as seeing someone with a bone sticking out of their shoulder after a bike crash.

You would think this would be an open-and-shut case—Enbridge’s lease on pipeline right of way has long since expired, and the tribe essentially moved to evict them, much like a landlord whose tenant had decided to start breaking the windows. A court finally agreed—though they delayed the judgment until 2026, a ruling Enbridge has of course appealed.

Mazzio’s film, tight in its focus on this one part of the story, doesn’t talk about the rest of the opposition to Line 5, from other tribal groups and also from a devoted and widespread citizen’s movement that has built across Michigan in recent years, gaining enough traction that in 2020 the state’s governor, Gretchen Whitmer, ordered the pipeline shut down. But it’s been in court ever since—most recently, a hearing last week in the 7th circuit of federal court, where both Enbridge and the Bad River band have filed suit, and where justices said they awaiting a filing of some kind from the federal government before making a decision. (The Canadian government, always eager to help the tarsands barons, argued that under international treaties the flow of oil through the pipeline should continue).

All of this is to say that the fight is both legal and political—which is usually the case. In both legal and political terms, tribal sovereignty should be enough to carry the day—as the movie makes quite painfully clear, right is on the side of the Bad River band in every possible historical sense. But, as becomes ever clearer in this country, the justice system is not fully separated from politics, and so the need to make broad coalitions is paramount. And those broad coalitions can worry about different, if linked, things.

In this case, for instance, the tribal argument for sovereignty, and the fears of local residents for the clear waters of the Great Lakes, are both potent and animating—they get a nucleus of people engaged because their very lives, and the places they live them in, are entirely at stake. In recent years the groups that form in these local places are called the “front line activists.”

But in a big country, where the fossil fuel industry always has clout, it also pays to get a wider assortment of people in on the fight: people who may live far from the shores of the big waters, and who may not have paid much mind to questions of tribal rights. So far, the best way to animate them has been to point out that these projects are also climate-killers. That is, if the oil spills then it is people along the Bad River and the Straits of Mackinac whose lives will be forever changed. But if the oil doesn’t spill, then the carbon it contains will spill into the atmosphere, where it will raise the temperature for everyone. Increasingly, this scrambles—in a helpful way—the idea of the “front lines.” If one is losing one’s home to wildfire in California because of desperate heatwaves, then one are on some kind of front line of the climate fight; if one can’t breathe in a New Delhi slum because the temperate has reached 120 degrees, then ditto. We all share the same enemy, which is the business-as-usual fossil fuel industry.

These kind of coalitions are never simple or easy to build, in part because the groups that organize people to care about the climate fight tend to be national or global, and hence bigger—if care isn’t taken, they can start to blot out the witness of the people closest to the trouble. But when care is taken, then alliances and even friendships blossom, and victories can happen—that is, I’d argue, the story of the fight over the Keystone XL pipeline (when indigenous people and midwest farmers and ranchers made common cause with each other, and with global climate groups) and the recent LNG wins, when similar partnerships formed between groups of inspired leaders along the Gulf of Mexico, and national and international environmental groups.

At any rate, watch the trailer for this movie, and then make a plan to see the whole thing. It’s a powerful chronicle of some of the saddest chapters in American history, and a hopeful picture of the emerging possibilities for power in the crucial fights of our time. And oh what beautiful country is at stake!

In other energy and climate news:

+An old friend, and really crucial climate voice, died recently. Ross Gelbspan had already retired from a long and successful career at the Boston Globe when he took up global warming. His book, Boiling Point, published in 1997, was one of the first to go after the emerging climate denial industry, and I can say that I greeted it with great personal relief—it was one of the first good books on climate change in the decade after I published The End of Nature, and what a relief to have a fellow writer to talk to and work with. Brendan DeMelle in DeSmog Blog published an excellent remembrance

Kert Davies, one of the world’s leading experts on climate denial (and a dear friend of mine since 2000), recalled to me that, “In the 1990s, Ross was our ‘Yoda’, guiding a new generation of investigators, who continue to this day trying to expose and dissemble the climate denial machine.”

That resonated with me especially since I wouldn’t be doing this work if it weren’t for Ross either. His 1997 book, The Heat Is On, was my personal introduction to the climate denial phenomenon. I met Ross in 1999 when he spoke at a Boston training for the Public Interest Research Group, and we bonded instantly when I showed him my dog-eared and tattered copy and asked him to sign it. Imagine my surprise when I joined DeSmog in 2008 and learned that Ross had inspired its creation.

+Nifty campaign: Environment America has noticed that FedEx has 5,000 warehouses in the U.S., and that they could and should put solar panels on top of them. So as a reminder, they’ll give you some “Go Solar” labels you can put on your FedEx packages

+Two new words—’fossilflation’ and ‘climateflation’—in a new report from a British think tank arguing that the rise in prices around the globe is increasingly a function of the fossil fuel industry.

In this context, orthodox monetary policy is counterproductive to achieving price stability, as well as governments’ economic, social and environmental objectives. Increasing interest rates fails to address the core drivers of rising energy and food prices, disproportionately hampers investment in capital-intensive green projects, and reduces government’s fiscal space. Instead, central banks should factor environmental considerations into the conduct of monetary policy and explore greater macroeconomic policy coordination with fiscal and industrial authorities. New international monetary arrangements will also be necessary to secure price stability and a just transition

+A fascinating report from scientists on the preferred speed for decarbonization: “fast,” or, a little more eloquently:

The Climate North Star project offers a path forward, integrating the fields of forestry, soil science, energy and materials management to maximize the speed of transition to a fossil fuel-free world, with the aim of completely decarbonizing the global energy system by 2035. The plan also emphasizes climate justice as a critical element of decarbonization efforts.

“We have run out of time for slowly weaning the world off of fossil fuels,” says David Merrill, project director for Climate North Star. “We see new examples every day of the damage being caused by the climate crisis: flooding, wildfires, drought, storms, record heat. This is an emergency, and we must move swiftly away from the climate status quo before it’s too late. Climate North Star can be the guide for how we get to where we need to go.”

+Major kudos to Michael Mann, veteran climate scientist, who won a million-dollar verdict from two bloggers who smeared him a decade ago. As the Washington Post reported:

The verdict is a dozen years in the making for the climatologist, who for decades has been a target of right-wing critics over his famous “hockey stick” graph.

Early in his career, Mann used data from tree rings, ice cores and coral reefs to show global temperatures were relatively stable until the Industrial Revolution. But after humans started burning fossil fuels in large quantities, Mann and his colleagues found, temperatures spiked over the past century.

Today, Mann is one of the most famous climate scientists in the country, having written half a dozen books, appearing on numerous TV shows and amassing more than 200,000 followers on X (formerly known as Twitter). As a public figure, he faced a high bar during the nearly month-long trial to prove his defamation claim.

+Remarkable new study from Connor Chung and Dan Cohn at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis finds that a decade of underperformance for fossil fuel stocks means that they’re no longer nearly as important to market indices as they used to be

Across index families, geographies, and target markets, excluding fossil fuels has led to modestly superior returns over the past 10 years, in both absolute and risk-adjusted terms.

The market for lower-carbon passive investing has matured significantly. Indices that reduce fossil fuel exposure are proving investable and passing fiduciary tests; transaction costs to implement new indices are proving affordable; and investment products benchmarked to them are proliferating.

There is good reason to believe that this is a durable market trend. Fossil fuel companies once generated shareholder value based on sound underlying fundamentals. More recently, their profitability has become dependent on volatile forces outside their control. The traditional value thesis underlying the industry—that the fossil fuel industry and economic growth are inextricably linked—is eroding. Facing increased competition between fossil fuel producers and from cheaper alternative technologies, the industry is ill-prepared to manage shareholder value in the coming years.

These kinds of adjustments to a new energy future are occurring across the economic landscape: an upcoming webinar is designed to help businesses navigate the new rules

+Transforming the food system may be a task second only to transforming the global energy regime—and we better do them at the same time. A vast new report on the parameters of such a switch imagines “a global effort to transform current food systems into a global system that produces healthy, nutritious food without sacrificing a livable environment, meets the needs of those working in agriculture and lifts upthe world’s poor and hungry.” If it happened, according the modeling in the study,

A shift to environmentally sustainable production in agriculture reverses biodiversity loss, reduces demand for irrigation water and almost halves nitrogen surplus from agriculture and natural land (i.e. land that has not been altered or developed for human purposes).

The food system becomes a net carbon sink by 2040. As part of a larger sustainability transformation which includes the energy sector, this helps to ensure that global warming is limited to well below the 1.5 degree C Paris Climate target by the end of the century, with peak warming barely exceeding 1.5 degree C

+Rising temperatures mean forests need to move—but roots make that difficult. Enter “assisted forest migration,” about which you can attend a webinar!

+Two brave people quit the climate advisory council to the Export Import Bank last week—because the bank simply wouldn’t listen to climate advice. As the Times reported

They described mounting frustration among climate advisory board members, who say they are being kept in the dark about upcoming fossil fuel loans and blocked from making recommendations about whether to approve or even modify a particular project.

At least two more climate advisory board members are considering stepping down, according to the officials.

Mr. Biden’s aides have expressed concern about the direction of the bank, which has consistently flouted a 2021 presidential order that government agencies stop financing carbon-intensive projects overseas.

+What happens if you have a really good year at Royal Bank of Canada, one of the five biggest lenders to the fossil fuel industry? They send you on a big cruise

Richard Brooks, of Stand.earth, whose non-profit group tracks the climate bona fides of the country’s big banks, likens the RBC flights and at-sea voyage to “a carbon bomb cruise.”

RBC declined to comment on the carbon intensity of its cruise rewards, but said such trips are “an important way for RBC to recognize and reward a select number of employees whose efforts have made an exemplary and positive impact for our clients, communities and colleagues during the past year.”

RBC spokesman Andrew Block also said the cruises offered “a learning and development opportunity.” He did not elaborate.

Brooks thinks RBC and other big banks and financial services companies who offer such trips should reconsider them, saying what was considered “normal behavior” 5, 10 or 30 years ago may no longer be appropriate amid a climate crisis.

+An important piece from the reliable journalist Alexander Kauffman on the latest effort by the fossil fuel industry to undermine the energy transition—they’re doing their best to make sure that new building codes calling for electrification don’t come into effect.

The International Code Council, the nonprofit organization responsible for writing widely adopted model building codes, broke its own rules to allow natural gas trade associations make the industry’s case for scrapping provisions for electric appliances and car chargers from the latest update to the codebook, HuffPost has learned.

Long accused of inappropriately chummy ties with the industries its rules regulate, the ICC late last year abruptly changed its own written policies to give the gas groups twice as much time to file appeals against codes they don’t like, and to skip a key bureaucratic step meant to provide oversight to avoid frivolous challenges, according to public documents and interviews with four sources with direct knowledge of the process.

The legitimacy of the entire building code system — already eroding, after recent changes to the process dampened hopes for more ambitious, greener codes — may now be at stake. Some experts involved in writing the latest codes say they may abandon the process altogether, in favor of forging a new national model that can more easily slash energy usage and cut back on planet-heating emissions.

The ICC had put a new approval process in place for energy codes in 2021, after industry groups balked at the most climate-friendly code in years. This new system put trade associations representing fossil fuel interests and real estate developers on equal footing with public officials from elected governments. Now, to advocates of stricter codes, it looks like the industry players are rigging the code-writing process even more.

“It’s a scandal,” said Mike Waite, the director of codes at watchdog American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy and a volunteer who helped author this year’s commercial building codes.

+A new report from the Clean Air Task Force adds to the weight of evidence that natural gas is no cleaner than coal. Exporting the fracked gas is particularly problematic:

Even where there is a slight benefit of gas vs. coal, our life cycle analysis shows that the use of unabated natural gas for power generation in developing countries is not consistent with achieving climate goals. When evaluating how much gas would be needed under Paris Agreement-compatible scenarios, another recent study concluded that long-term planned LNG expansion is not compatible with the Paris climate targets of 1.5 °C and 2 °C due to oversupply of gas and limited availability of future coal-based generation to displace.

Oh, and Mark Wolfe and Tyson Slocum explain in the pages of Newsweek why limiting LNG exports helps U.S. consumers big time

+Attention! Important blimp update!

Hybrid Air Vehicles Ltd, a UK-based leader in sustainable aircraft technologies, has today announced an aircraft reservation agreement with Grands Espaces, a French eco-tourism company founded by renowned Arctic scientist and author, Christian Kempf.

Today’s announcement is another step forward in Airlander 10’s entry into service programme, growing an order book already in excess of £1bn and building momentum towards the start of production this year.

By bringing together Hybrid Air Vehicles’ Airlander 10, the world’s most efficient large aircraft, with Grands Espaces’ sustainably minded and pioneering vision of tourism, the reservation will enable the expansion of tourism into new and less-explored regions with an ultra-low emissions aircraft.

Airlander’s ability to take-off and land from any reasonably flat surface, including water and ice, and the minimal requirement for fixed infrastructure will help to sustainably expand Grands Espaces’ services, offering improved access to areas that cannot be easily reached by conventional aircraft or boat, while offering a unique experience for guests.

Well, that’s an indulgence. But hopefully it will help build this industry—and boy does it sound sweet.

The Line 5 pipeline “as grotesque and scary as seeing someone with a bone sticking out of their shoulder after a bike crash” was discovered by accident —70 yrs & ticking!

Thank you Bill for exposing the horror of Line 5 at Bad River. The Bad River movie is a must see!

Climate change is so important that to see well-meaning efforts going into reducing supply of fossil fuels project by project instead of badgering politicians to "screw their courage to the sticking place" and just pass a tax on net CO2 emissions, is very disheartening.