“Climate week” is about to start in New York City, and my inbox has been awash in the latest press releases about start-ups and noble initiatives and venal greenwashing. Much of it’s important, and I’ll get to some of it later in this newsletter. But there’s a big new study that came out yesterday in Science that sets our crucial moment in true perspective. Let’s step back for a moment.

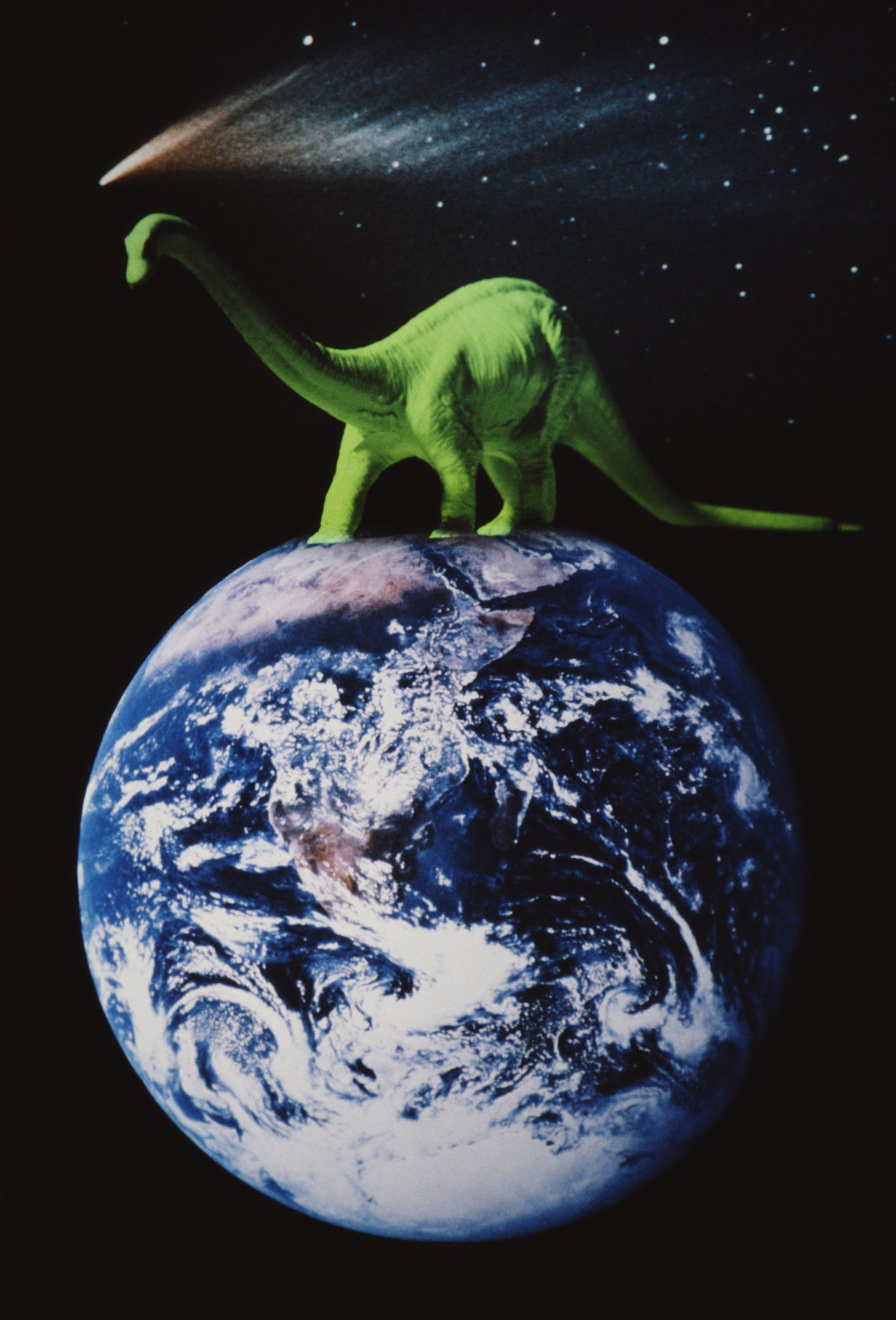

This new study—a decade in the making and involving, in the words of veteran climate scientist Gavin Schmidt “biological proxies from extinct species, plate tectonic movement, disappearance in subduction zones of vast amounts of ocean sediment, and interpolating sparse data in space and time”—offers at its end the most detailed timeline yet of the earth’s climate history over the last half-billion years. That’s the period scientists call the Phanerozoic—the latest of the earth’s four geological eons (we’re still in it), and the one marked by the true profusion of plant and animal life. It’s a lovely piece of science, and it’s lovely too because it reminds us of all we’re heir to in this tiny brief moment that marks the human time on earth. So staggeringly much—strange and extreme and fecund—has come before us.

But it’s also scary as can be, for two big reasons.

The first is that it shows the earth has gotten very very warm in the past. As the Washington Post explained in an excellent analysis yesterday, “the study suggests that at its hottest the Earth’s average temperature reached 96.8 degrees Fahrenheit (36 degrees Celsius).” Our current average temperature—already elevated by global warming to the highest value ever recorded—is about 60 degrees Fahrenheit, or 15 degrees Celsius. For most of the 500 million years the study covers, the earth has been in a hothouse state, with an average temperature of 71.6 Fahrenheit, or 22 Celsius, much higher than now. Only about an eighth of the time has the earth been in its current “coldhouse” state—but of course that includes all the time that humans have been around. It is the world we know and we’re adapted to.

In every era, it’s increases in carbon dioxide that drive the increases and decreases in temperature. “Carbon dioxide is really that master dial,” Jess Tierney, a climate scientist at the University of Arizona and co-author of the study, said. And so the study makes clear that the mercury could go very high indeed as humans pour carbon into the sky. We won’t burn enough coal and oil and gas to reach the very highest temperatures seen in the geological record—that required periods of incredible volcanism—but we may well double the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, and this study implies that the fast and slow feedbacks from that could eventually drive temperatures as much as eight degrees Celsius higher, which is more than most current estimates. Over shorter time frames the numbers are just as dramatic

Without rapid action to curb greenhouse gas emissions, scientists say, global temperatures could reach nearly 62.6 F (17 C) by the end of the century — a level not seen in the timeline since the Miocene epoch, more than 5 million years ago.

Now, you could look at those numbers and say: well, the earth has been hotter before, so life won’t be wiped out. And that’s true—there’s probably no way to wipe out life, though on a planet with huge numbers of nuclear weapons who knows. But these temperatures are much higher than anything humans have experienced, and they guarantee a world with radically different regimes of drought and deluge, radically different ocean levels and fire seasons. They imply a world fundamentally strange to us, with entirely different seasons and moods—and if that doesn’t challenge bare survival, it certainly challenges the survival of our civilizations. Unlike all the species that came before us, we have built a physical shell for that civilization, a geography of cities and ports and farms that we can’t easily move as the temperature rises. And of course the poorest people, who have done the least to cause the trouble, will suffer out of all proportion as that shift starts to happen.

But that’s not the really scary part. The really scary part is how fast it’s moving.

In fact, nowhere in that long record have the scientists been able to find a time when it’s warming as fast as it is right now. “We’re changing Earth’s temperature at a rate that exceeds anything we know about,” Tierney said.

Much much much faster than, say, during the worst extinction event we know about, at the end of the Permian about 250 million years ago, when the endless eruption of the so-called Siberian traps drove the temperature 10 Celsius higher and killed off 95 percent of the species on the planet. But that catastrophe took fifty thousand years—our three degree Celsius increase—driven by the collective volcano of our powerplants, factories, furnaces and Fords—will be measured in decades.

Our only hope of avoiding utter ruin—our only hope that our western world, in the blink of an eye, won’t produce catastrophe on this geologic scale—is to turn off those volcanoes immediately. And that, of course, requires replacing coal and gas and oil with something else. The only something else on offer right now, scalable in the few years we still have to work with, is the rays of the sun, and the wind that sun produces, and the batteries that can store its power for use at night.

Another new analysis this week, this one from the energy thinktank Ember, shows that 2024 is seeing another year of surging solar installations—when the year ends there will be 30% more solar power on this planet than when it began. Numbers like that, if we can keep that acceleration going for a few more years, give us a fighting chance.

That’s what all those seminars and cocktail parties and protests in New York over the next week will ultimately be about—the desperate attempt to keep this rift in our geological history from getting any bigger than it must. As this new study once more makes clear, raising the temperature is by far the biggest thing humans have ever done; our effort to limit that rise must be just as large.

We need to stand in awe for a moment before the scope of earth’s long history. And then we need to get the hell to work.

In other energy and climate news:

+Flooding everywhere—in central Europe, where the Danube has burst its banks at Budapest, in Africa where at least 621 people are dead in the Lake Chad region, and in the Carolinas where a storm that wasn’t even strong enough to merit a name nonetheless dumped 18 inches of rain in 12 hours. As Mark Gongloff points out,

Meteorologists say this sort of event has a 1-in-1,000 chance of happening in any given year; something more commonly known as a “thousand-year flood.” But the moniker doesn’t quite fit when you consider similar disasters also hit the area in 1984, 1999, 2010, 2015 and 2018. Along with the latest flood, that’s five in just 25 years.

Despite lacking a name, the rainstorm may have caused $7 billion in damage, private meteorological service AccuWeather estimated. Not counting that, there have been 20 extreme-weather events in the US so far this year wreaking $1 billion or more in damage, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, making it already the third-busiest year on record, with half of a hurricane season still to go.

+The world’s bankers are making it very clear that their responsibility does not extend to helping solve the climate crisis. A new paper from the Institute of International Finance, as Bloomberg puts it, makes clear that

Instead of indicating that the money required to green the economy is ready to flow, industry leaders now say their first priority is delivering financial returns for clients—and that means energy-transition investments will only be undertaken if they’re considered profitable.

“Expecting banks collectively to rapidly reallocate their portfolios may not be compatible with maintaining a profitable, diversified business model,” the IIF said. “It also neglects the reality of a bank’s commercial relationships, considering that banks can’t force clients or counterparties to take finance for certain activities.”

Along these lines, a new analysis from the folks at Stand.Earth, explains how Citibank’s funding of new LNG export terminals in the Gulf South is not just fueling the climate crisis but doing devastating damage to local communities. As the remarkable activist Roishetta Ozane says in the foreword:

Participating in this report has compelled me even more to bring attention to the deeply troubling reality of environmental racism and its devastating impacts on communities like mine: low-income, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. As a mother of six children, some of whom battle health issues directly caused by long-term exposure to industrial pollution, and as a survivor of multiple climate-induced disasters that once rendered my family homeless in Southwest Louisiana, this issue strikes at the core of my being

+The biggest problem for new solar farms in the US is connecting to the grid. One solution, at work in Tim Walz’s Minnesota: locate your field of panels next to a defunct coal-fired power plant, which by definition has all the wiring you’d ever need:

The US could essentially double the capacity of its electrical grid overnight by plugging renewables projects into old fossil fuel power plants, University of California Berkeley researchers found, whether they be coal, gas or oil. And projects could be plugged into existing plants, not just ones that are retiring.

“This should be one of the main strategies that we adopt going forward, because we already have so many existing assets, so much grid infrastructure and we don’t want to just throw them away,” said Umed Paliwal, a senior scientist at UC Berkeley and a lead author of the study.

+Always on the lookout for a good analogy—here’s the Trojan Horse story, as retold by the Wildlife Conservation Society

Late in the war, when Odysseus conceived the ruse of gifting to Troy a giant wooden horse, filled with the invading armies’ deadliest soldiers, Cassandra knew it was a trick to get the Trojans to bring the enemy inside the city gates. She shouted the truth at the top of her lungs, lit a torch and ran toward that wooden beast to burn it to the ground and incinerate the enemy within. But the people of Troy held her back. They loved that horse. And they knew Cassandra was out of her mind. Until that night, when the finest warriors ancient Greece could muster stealthily emerged from the hollow belly of the horse and destroyed their city.

Like the ancient Trojans, we’re in denial. And like Cassandra, today’s climate scientists are tolerated but the urgency of their facts and fears is ultimately dismissed.

The question at hand is whether, unlike the Trojans, we have the wherewithal to change our fate. The odds are not in our favor. Time is short. Because we’ve waited so long to act decisively, we now have just a few years left before we’re fully committed to a future hotter than any that has existed on earth since humanity emerged.

+Feckless governor watch: New York’s Kathy Hochul has seen her popularity slide to record lows after she executed her double-cross on Manhattan congestion pricing; meanwhile, in California, Gavin Newsom can boast of a more robust environmental record, but Sammy Roth of the LA Times lays out ten big decisions he has coming up that will really establish his green cred—or not

For instance, Senate Bill 1374, which would

give schools and apartment buildings with solar the same right to “self-consumption” enjoyed by single-family homes, allowing them to lower or cancel out their utility payments when the sun is shining.

Sounds like an easy decision for a governor who calls himself a climate champion.

Then again, Newsom didn’t stop his appointees from setting up this poor system in the first place. And Becker told me he thinks there’s a “good chance” Newsom vetoes the legislation, based on rumors he’s heard.

Why would the governor do that? Presumably for the same reason he’s undermined rooftop solar in the past: It’s opposed by powerful utility companies, which shortsightedly see the technology at odds with their business model, and by powerful utility labor unions, which don’t like that most rooftop solar installers are nonunion.

+The nation’s first carbon capture and storage plant is…corroding after seven years in use, according to a report in Desmog Blog

Because of the risks captured carbon poses, including risks to the nation’s groundwater supplies, federal rules generally require Class VI wells to be monitored the entire time they’re in use, plus 50 years after — so the discovery of issues at ADM’s project this early on could be a sign of significant problems to come as carbon capture and monitoring wells age.

“This incident puts an exclamation point on concerns communities across the country have been raising for years about the dangers the CCS industry poses to public safety and drinking water,” Food & Water Watch policy director Jim Walsh said in a statement today responding to the news.

“Waiting at least a month to notify the public of this violation is especially egregious given the major health and safety risks associated with carbon dioxide contamination in air and water,” Walsh added. “The lack of transparency from EPA about this leak is alarming but unfortunately in line with a failure of federal oversight for the entire carbon capture industry.”

+This week’s half-point rate cut by the Fed is good news for the renewables industry, Matthew Zeitlin reports

High interest rates, which drive up the cost of borrowing money, have an outsize effect on renewable energy projects. That’s because the cost of building and operating a renewable energy generator like a wind farm is highly concentrated in its construction, as opposed to operations, thanks to the fact that it doesn’t have to pay for fuel in the same way that a natural gas or coal-fired power plant does. This leaves developers highly exposed to the cost of borrowing money, which is directly tied to interest rates. “Our fuel is free, we say, but our fuel is really the cost of capital because we put so much capital out upfront,” Orsted Americas chief executive David Hardy said in June.

Trump's energy policy - to the extent he has one - is to radically cut back on EV, solar, wind, geothermal, and battery storage, allowing China to surge even further ahead. In Trump's plan, the US is to boost gasoline & diesel burning cars, and continue extracting and burning as much oil, gas and coal as possible for as long as possible. [Trump will be dead before the very worst climate effects show up, but he's never cared about anyone but himself.]

So we have to get Harris in the White House if humanity is to have any chance at all of surviving in some form other than a new Neolithic Age.

"Time is short. Because we’ve waited so long to act decisively, we now have just a few years left before we’re fully committed to a future hotter than any that has existed on earth since humanity emerged." The time for a tax on net CO2 emissions was the '70's, but better late than never.