When movements work

Boston's nifty new mayor validates a decade's hard work by divestment activists with the stroke of a pen

When people wonder how movements work—how they accomplish things, even though they don’t begin with money or influence—it’s worth thinking about events this morning in Boston City Hall.

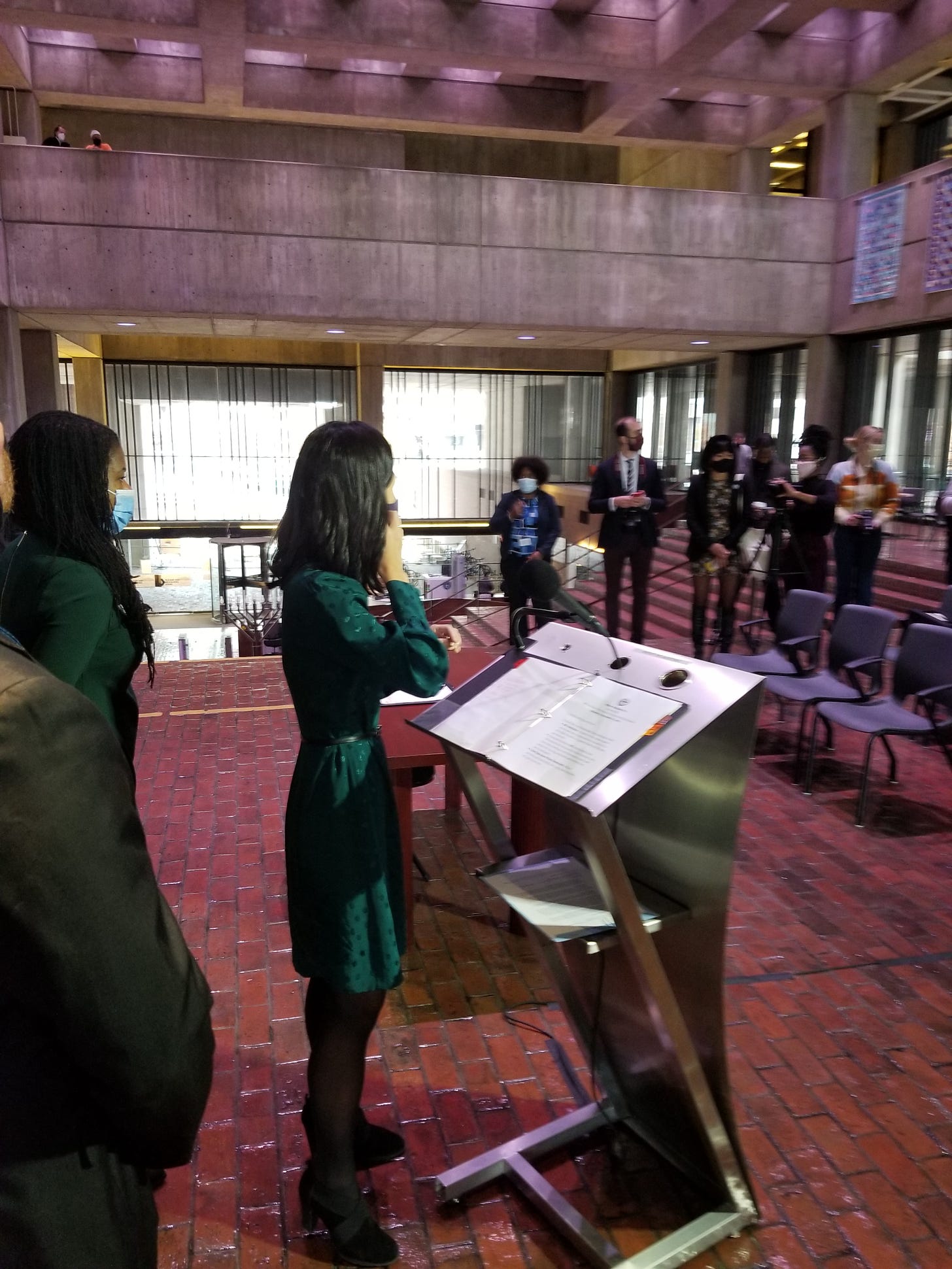

There, amidst a large and happy crowd of witnesses, the city’s remarkable new mayor Michelle Wu signed the first ordinance of her mayoralty: an act divesting the city’s finances from fossil fuel.

[If organizing feels important to you, check out Third Act, our effort to organize Boomers and the Silent Generation. My share of the subscription revenues from this newsletter helps support our early efforts]

As she signed it, I flashed back on many things. The night in November of 2012 when Naomi Klein and I, and lots of our friends and colleagues, welcomed 2,500 people to the Orpheum Theater for the Boston stop of the Do the Math tour that helped launch the divestment movement. We’ve gotten lots of credit for that work—but in truth it was a little like Tom Sawyer whitewashing the fence out front of Aunt Polly’s house. We’d gotten lots of inspiration from those who had come before—the South African divestment movement, for instance (and one of its important players, Bob Massie, was on hand for this morning’s ceremony). And before we knew it, people had taken up the fight at thousands of institutions, and each one of those fights added to the power of the whole. So—in Massachusetts alone—there were students at Lesley and Harvard and MIT (where they did a hundred-day sit-in). At BU and Wellesley and BC and UMass (Varshini Prakash, who runs the Sunrise Movement and so is as responsible as anyone in the country for the Build Back Better bill cut her teeth divesting UMass). A local financier, the hedge fund pioneer Jeremy Grantham, assembled compelling data to show that divestment was financially prudent. Groups like 350 Mass and the local chapter of the Sierra Club went to work on the state legislature; and at the same time those people were working with other activists on overlapping projects. The Rev. Mariama White-Hammond, for instance, was a pioneer in local environmental justice work; she was arrested in 2017 trying to block a gas pipeline. And now she’s the city’s official Chief of Energy, Environment, and Open Spaces, making change from the inside—she spoke powerfully at today’s signing ceremony.

The point I’m trying to make is simply that you can never really steer a movement. If it gets big enough to matter, it will roll on with its own power and beauty. People of good heart like Michelle Wu see it, understand it, and use the power we’ve given them to make it happen. Eventually it comes to seem obvious: New York and London and Paris have now divested, and Glasgow and Rio and many more. We’re at $40 trillion in endowments and divestments that have divested; that’s enough to have helped change the debate. And each new step makes it easier: the news from Boston City Hall will echo at the headquarters, say, of Fidelity, with $4.2 trillion in assets under management, which is about six blocks away.

One can help propel this work along—goodness knows I haven’t stopped giving speeches and writing articles and lobbying for its success—but I long since understood that I would never meet more than a hundredth of the people who have made this vision work. And that is a remarkably sweet thing to know: none of this depends on any one of us, all of it depends on all of us.

It’s never easy; two steps forward, often followed by a pratfall. Just today, as we were celebrating the Boston news, the Los Angeles Times editorial board published an editorial attacking divestment in California. It was a farrago of the long-since-demolished arguments (it’s amazing to think, for instance, that there are still people arguing that divestment comes at an economic cost; literally dozens of studies have made the opposite clear. And anyone who thinks that ‘engaging’ with Exxon is an effective strategy is a kind person unmoved by thirty years of bitter experience). But I have no doubt people will assemble themselves to take it on, writing the letters and emails that will eventually prompt a rethinking. The power of a good idea, pushed forward by good people, is much stronger than industry or institutions usually expect.

That’s different from saying it will happen fast enough. I do wish we’d gotten started sooner.

Congratulations...even if advances happen 1 step forward and 1 step to the side, you've achieved far more than 4 decades of Congress.

You have given me the gift of Gratitude, today. TY