Worse Living Through Chemistry

Total Mass of Plastics on Earth Now Exceeds Total Mass of All Mammals

I don’t mean to add to anyone’s psychic burden—there’s enough bad news to go around this week, as a mood of semi-despair seems to settle over a country still plagued by a plague, and by a political system so clogged and sclerotic that, forced to choose between the filibuster and democracy, it decided the former was preferable.

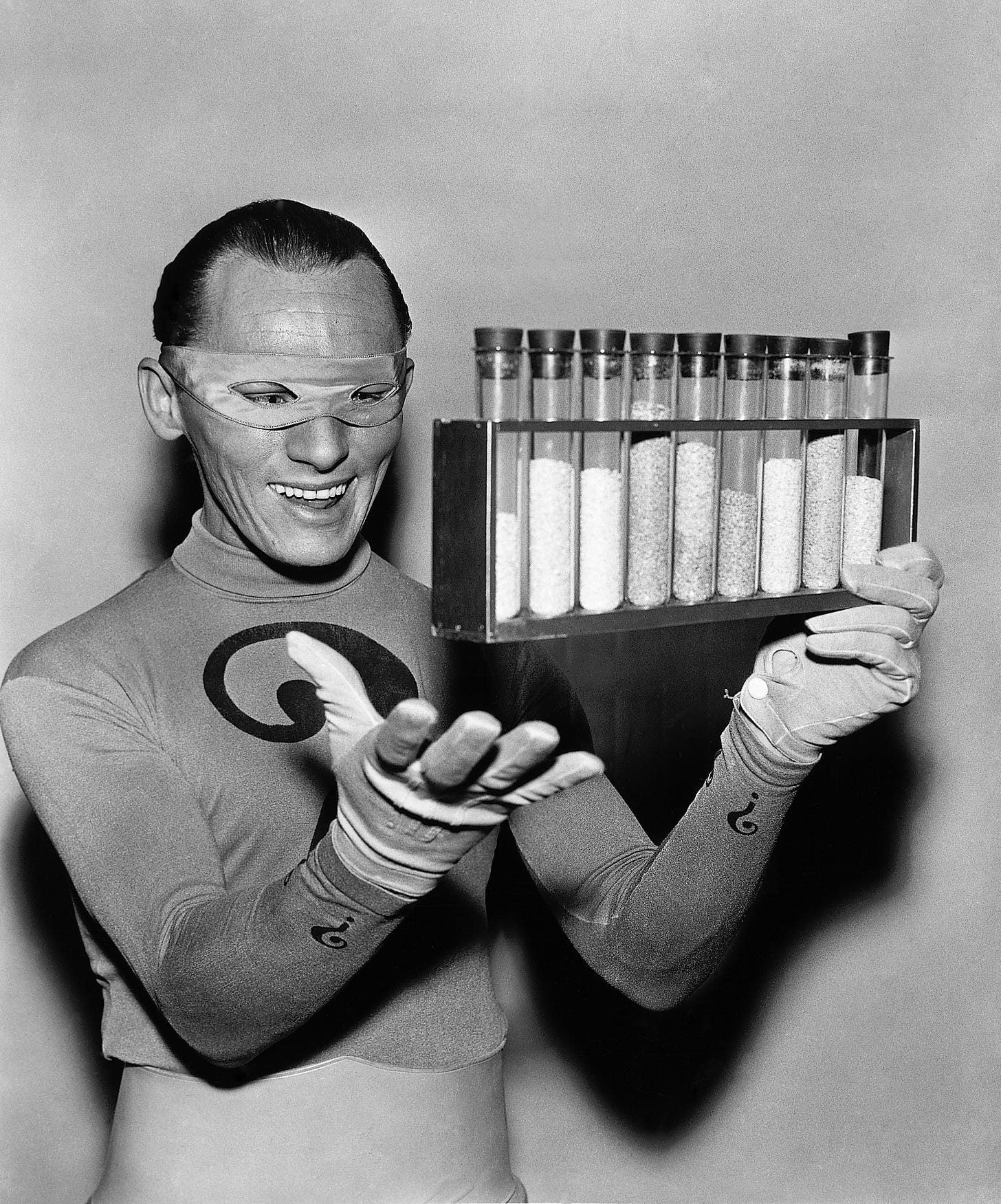

But the actual physical world doesn’t care about our psychic burdens; it cares about physical burdens, like the one we’ve imposed by fifty years of pumping chemicals into the air, the soil, and the water. Writing in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, a team led by researchers from the Stockholm Resilience Center concuded that “the increasing rate of production and releases of larger volumes and higher numbers of novel entities with diverse risk potentials exceed societies’ ability to conduct safety related assessments and monitoring.” By novel entities, they mean chemicals that “are novel in a geological sense and that could have large-scale impacts that threaten the integrity of Earth system processes.” As the team at Beyond Pesticides points out, “the novel entities that have so suffused Earth’s air, water, ecosystems and biodiversity, wildlife, and human bodies comprise 350,000 synthetic chemicals — including persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) — found in plastics, synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, industrial and manufacturing compounds, antibiotics, degreasers, cleaning agents, and many other commodities. Only a tiny fraction of those 350,000 compounds has been assessed for safety, yet many are now found in human tissues.”

The study didn’t get much attention in the general press—an article in the Guardian, but as far as I could tell that was about it. But the numbers are so striking that they need to be part of our basic understanding of this time on earth: “There has been a fiftyfold increase in the production of chemicals since 1950 and this is projected to triple again by 2050,” said Patricia Villarrubia-Gómez, a PhD candidate and research assistant at the Stockholm center who was part of the study team. “The pace that societies are producing and releasing new chemicals into the environment is not consistent with staying within a safe operating space for humanity.”

Indeed, the Stockholm group has been tracking what they consider nine planetary boundaries, and this is the fifth that we have now breached, the others being habitat destruction, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, and of course temperature rise. “There’s evidence that things are pointing in the wrong direction every step of the way,” team member Bethanie Carney Almroth of the University of Gothenburg told the Guardian. “For example, the total mass of plastics now exceeds the total mass of all living mammals. That to me is a pretty clear indication that we’ve crossed a boundary.”

More news from the physical world this week

+Exxon’s new pledge to go carbon zero by 2050 was such a transparent piece of greenwashing that journalists had no trouble seeing through it: ABC News, for instance, headlined its story “Expert’s Slam Oil Giant Exxon’s Net Zero ‘Ambition,’” pointing out that it doesn’t cover the emissions caused by, um, using its products.

As the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions from the oil and gas industry stem from the consumption of its products, scientists and environmental researchers have slammed the headline-grabbing announcement from the U.S. energy giant as ineffective and insufficient at a time when climate change is already harming communities around the globe.

+Shell’s new ‘carbon capture’ plant appears to be releasing more greenhouse gases than it sequesters. Oh well.

+Gus Speth is one of the wisest voices of the environmental movement, a leader all the way back to the first Earth Day; it’s well worth reading his op-ed in The Hill arguing that “this must be the year of climate action.”

The climate movement also needs to join forces with those who are fighting to save our democracy, including human rights and voting rights in America. We need to leave the silo of traditional environmental advocacy and get into the thick of electoral politics, an area of historical neglect by environmentalists.

+Catching up a little here, with a remarkable series from the Portland Press Herald and the Boston Globe on the lobster business in a fast-warming Gulf of Maine. Maine fishermen, the series begins,

need only look to the south to see how Maine’s boom times could end. In the once bountiful waters off Connecticut, a single full-time lobsterman remains – but today he fishes in a watery graveyard. The lobster catch has also waned in the hard-hit fishing ports of Rhode Island and the south coast of Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, the Globe—one of the country’s great historic newspapers—this week announced it was opening up a full-time climate desk.

+Ilana Cohen offers a compelling account of her decision to break up with Bank of America because of its funding for fossil fuel destruction. My only caution: unless you have a national magazine audience, don’t do this on your own: instead, join us on Wednesday’s national monthly call for Third Act, where we’ll be discussing how to pressure the banks as a joint project!

A somewhat somber chapter from our epic nonviolent yarn. If you need to catch up on the first 40 chapters of The Other Cheek, check out the archive.

Everyone at SGI—students and staff—had risen early to watch the Dalai Lama’s interfaith gathering from Ahmedabad. It had started at 5 p.m. there to avoid the worst of the day’s heat, which meant it was 5:30 a.m. when the broadcast went live on the screen in the Mandela auditorium. Students were still settling in when the singer started in on Here Comes the Sun, and no one could figure out why she stopped, or why the whole assembly seemed to be heading for the exit.

It took CNN International ten or fifteen minutes to locate someone’s cellphone video of the piglets squealing amid the Muslims, and to assemble a crew of experts to explain exactly why it had been so insulting.

“Swine are unclean to the Islamic faith, and also to Orthodox Jews,” said a man from the American University in Beirut, identified onscreen as a “religion scholar.” “This was a deep insult, and I wouldn’t be surprised if this shuts down the entire conference. The Dalai Lama has to be feeling—sheepish,” he said, as the rest of the talking heads smiled in unison.

With the conference adjourned, Maria stood up and turned off the monitor, sending everyone to breakfast, and telling them to reconvene afterwards for a discussion.

Because they were up so early, they were sharing the dining hall with this week’s yoga-with-trees retreat—the series had become so popular that most of the center’s other holistic programs had been put on hold, and each Sunday a new crew of people would arrive to channel the inner essence of the aspens that grew around the campus. By now everyone at SGI was used to middle-aged men sitting cross-legged in front of trees, or women doing a ‘re-childing’ workshop (MK and Cass’s idea originally, though they’d thought of it as a joke) that involved building the tree fort only boys had been able to erect when they were young. The guests were quiet and paid well, and they helped distract attention from SGI’s real mission as a center for activist training and coordination; the main drawback was that the cafeteria no longer served maple syrup, on the grounds that it was widely considered ‘tree blood’ in the tree-yoga community. Today the yogis were in silent mode, meditating on the way that the food they put in their mouths was like the nutrients sucked up by aspen roots that made its steady way right to their outermost leaves. The SGI students mostly respected the silence, in part because they were groggy from being up so early, and in part because the events in India had stunned them.

Almost no one wanted to talk when they filed back into the auditorium, either. Maria reviewed briefly the story of the morning’s pig problem, and then the school’s defaced posters; she asked for reactions to either one.

“I think it’s sad?” said Memory. “People should be kinder to each other, especially monks?”

No one else responded, and the silence grew. The faculty, seated in a row at the table on the small stage, kept a steady gaze on the students, just waiting.

Finally Jukk broke the silence. “Personally, I’m glad those monks did what they did,” he said. He stood up, clutching a napkin. “I brought a piece of bacon from breakfast. If I toss it at you Anand, what’s going to happen? Is it going to hurt you? It’s . . . bacon.” He looked quickly—triumphantly—over at Allie, but she was looking down at the floor. He went on, a little less brashly.

“Let’s face it. Religion is outmoded. It’s from the days before science, when people needed some explanation for the world. But no thinking per-son could endorse it.”

“He’s right, you know,” said Aadit. “It’s always been violent—think about the crusades. Now it’s Islam, mostly. Every time there’s a shooting or a bombing, there’s always someone yelling ‘Allahu Akbar.’ What does that tell you?”

“And everyone here is always going on about women’s rights, women’s rights—who do you think is keeping women down?” said Jukk, more and more exercised. “I mean, Yasmin has to keep her hair in a scarf. What’s wrong with hair.”

Yasmin looked stricken, and several of the students moved to comfort her.

“Shut up Jukk,” said Winston Liu. “You’re being an asshole.”

“Oh, good argument!” said Jukk.

“Jukk’s right—it’s not a very good argument,” said Professor Kinnison, rising from his chair. “Tolerance is indeed a virtue, but is there no one here who wants to make an actual case for the role of religion?”

When no one answered, he continued: “I’m not completely surprised. Fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, five hundred years ago almost everyone in this world was committed to one religious tradition or another—it would have been how they understood their lives. And for most people that’s still true. But for the educated—and especially for the progressive—there’s been a fast drift away from faith. Jukk, in Scandinavia less than five percent of people go to church—it’s irrelevant. The US is the most religious developed country on earth—but non-believers are the fastest-growing category of Americans, and that growth is concentrated among young people.”

“Pope Francis is a rock star,” said Tomas.

“True,” said Professor Kinnison. “But it doesn’t seem to have changed people’s perceptions of religion as much as, say, the ISIS bombings.”

“Or the Taliban,” said Aadit. “I mean, they tried to kill that girl who just wanted to go to school.”

“May I say something?” said a quiet voice from the end of the faculty table.

“We would be honored if you did, Professor Vukovic,” said Maria—and indeed the whole gathering was staring at the old man as he rose a little slowly to his feet. Except for Allie, the students knew him only as some kind of famous and ancient relic who never ever said a word.

“I am an atheist,” he said. “I have been most of my life. At first it was for ideological reasons—I was also a communist, and thought that religion was, as Mr. Marx put it, opium for the volk. I stopped being a communist before long, and I would very much have liked to stop being an atheist too, but I’ve never been able to encounter a god or gods. It is a great sadness—maybe the great sadness—of my life. Because most—not all but most—of the greatest nonviolent activists I’ve ever met have been people of deep faith. And, I might add, the most violent people of my lifetime—Hitler, Mao, Josef Stalin to whom I gave my allegiance when I was young—were persecutors of religion. Anyway, today I want to tell you a story about the single greatest nonviolent activist I ever met, a man named Gaffur Abdul Khan. I am . . . somewhat short of breath these days, and this is a long story, so I’ve asked my research assistant—my research assistants—to help me. Also, they know Powerpoint, which I do not. Goldfarb? Salgado?”

Cass and Allie, who’d been sitting together at the front of the hall, came forward, one standing at each elbow, and Allie pushed a button to lower a screen. When it was down, she poked at her computer for a second, and an image of a tall, handsome bearded man appeared in front of the hall.

“This is Gaffur Abdul Khan, born 6 February 1890 in what the British called the Northwest Frontier Province,” said the professor. “It’s that land on the border of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, the homeland of the Pathans, the precise people that caused such trouble to the Soviets, to the Americans, and basically to everyone else who tried to subdue them. First they caused great trouble to the British, and that is the story I want to tell.

“Gaffur Khan was born in the town of Utmanzai, twenty miles from Peshawar, now perhaps the greatest small arms bazaar in the world. His father was the khan—the chieftain—of the village, and a man of some wealth and standing, at least by the standards of his palce and time. Though like everyone else in the region they were good Muslims, his father sent him, despite the grumbling of the mullahs, to the Mission high school in Peshawar run by an Anglican reverend. Khan would say later that watching the brothers who taught at the school, seeing their love and generosity, had rubbed off on him—he would quote a Pathan proverb, “When a melon sees another melon, it takes on its color.”

Khan turned down service in the British military—an honor that few who had the chance rejected. Instead, he made the hajj to Mecca, and then began to wander the villages of the Pashtun region, setting up small schools so others could be educated. One day, in a remote village, he stopped in the tiny local mosque and didn’t emerge for a few days. He said later that as he prayed, the word “Islam” began to vibrate with meaning for him: ‘Surrender.’ Surrender to the Lord and know his strength. He began his work as a reformer in earnest. Between 1915 and 1918, says his biographer Eknath Easwaran, he visited every one of the 500 villages in the settled districts of the Northwest Frontier. He would sit with the villagers in each one, and talk about education, about community—and about the news beginning to filter out from the rest of India of what Gandhi had begun. At some point they began to call him Badshah Khan, the King of Khans.”

Professor Vukovic stopped, and sat down. He seemed worn, suddenly unable to talk. He glanced up at Cass and nodded.

“Well,” she began a bit hesitantly, “the British put him in jail for the first time in 1919, after they imposed martial law. When he got out, after six months, he went back to building schools, and was soon put back in jail. There’s a story I found when I was researching—he was locked up and one of the British officials told him he didn’t believe that he was actually nonviolent. Khan said he’d taken a vow because he’d read about Gandhi. ‘What would you have done if you hadn’t heard of Gandhi,’ he asked. Khan slowly bent two of the iron bars of the cell. ‘This is what I would have done to you,’” he said.

“That’s the part you need to understand,” said Professor Vukovic, still sitting down. His voice was thin, but urgent. “When I met him he was an old man, but still tall—he was 6’3—and strong. And the Pathans were—are—the most warlike people I’ve ever met. It’s a world of honor codes and violent revenge. Which makes the rest of the story . . .”

“It makes the rest of the story even more unlikely,” said Allie, who rested a hand on the professor’s shoulder. She switched the powerpoint to show a picture of a small crew of men and boys in red shirts. “Khan did a lot of amazing things. He founded more schools, he started the first magazine in Pushto, and he worked hard to liberate women; he didn’t believe in what they called purdah, secluding women, and he made sure that girls could be educated. But eventually, once he’d met Gandhi, he had his most important idea. For an army. The world’s first nonviolent army. They called themselves the Khudai Khitmatgar, the Servants of God, and their first declaration was “As God needs no service, but serving his creation is serving him, I promise to serve humanity in the name of God. And their second pledge was “I promise to refrain from taking violence and revenge.”

Cass took over from Allie. “These guys didn’t make ‘promises’ like you or me. These were vows. They meant them. They all had red shirts they wore. When Gandhi started making salt at the end of his march, there were huge demonstrations across India, and the British didn’t know what to do—the whole world was watching. But not in the Northwest Frontier. They sealed it off, they imposed martial law, there was no one there to see. No reporters. In Peshawar they had a demonstration, completely peaceful, but the British thought that if they gave in even a little bit the Pathans would run them out. So they started firing on the demonstrators.”

“This was at Kissa Khani Bazaar, the Storyteller’s Bazaar,” said Professor Vukovic. “I’ve been there.” He paused for a moment. “They shot and killed a number of people. No one fought back. Instead, the next line of red shirts pushed aside the bodies, and stood there, baring their chests. The British killed them, and then the next line came forward. This went on for hours, from 11 in the morning until 5 in the evening. Two hundred and fifty dead.” He seemed completely spent, and sunk back in his chair—Maria got up and stood behind him, whispering in his ear. He shook his head, and Allie resumed the story.

“The repression—well, it did the opposite of what the British wanted. Soon there were 80,000 members of the Servants of God. They shot them, they threw them down wells, they . . . dishonored them by making them take off their pants in public. But nothing worked—they stayed nonviolent.”

Cass showed a picture of the giant Khan towering over a frail Gandhi. “The British sent him to prison thousands of miles away in the main part of India, and when they released him they kept him exiled,” she said. “He lived at Gandhi’s ashram and became his great friend. In fact, they called him the Frontier Gandhi. And when the British finally let him return home, the first thing he did was arrange a visit for Gandhi.”

She looked over at Allie, who flipped up a picture of the two men in Peshawar. “When Gandhi came, he said it was the most important visit of his life. Wherever he went in India, he was mobbed by screaming crowds. Here, the Pathans by the tens of thousands stood by the roads, smiling, erect, and perfectly silent. Gandhi said they were the first people he’d ever met who’d really begun to understand non-violence.”

Anand Chowdury waved a hand. “How come we’ve never heard of him? I mean, I’m a Muslim, I’m from that part of the world, if this guy is so great why isn’t he famous?”

Cass said “I don’t completely get that part either. But it has to do with what happened when the British left India.”

“Exactly,” said Professor Vukovic. He was sitting straighter now, his voice a little stronger. Cass and Allie shared a look—they knew from the day he’d spent preparing the powerpoint that he could barely talk about the massacre at Kissa Khani; he’d told them it made him ashamed of himself simply to think of the strength of those people. Now that the story was becoming more scholarly, he was rallying, though his voice was still a little tremulous.

“When the British left India, the Muslim League demanded that the portions of the subcontinent where Islam predominated be separated out—that’s how Pakistan came to be born, and Bangladesh. Which was originally East Pakistan, but that’s another horrible story. Anyway, Gandhi—and Khan—hated this partition. Gandhi was fasting and praying, not celebrating, the night of India’s independence. Even though he was in his 70s he planned to walk across India to the Northwest Frontier to see Khan. But he was shot before he could go, by a fanatic Hindu who thought he was too soft on Muslims. Meanwhile the Muslim League hated Khan as much as they hated the British—the Pakistanis put him in jail right away as a security risk, and he spent maybe half the rest of his life there. Every time they let him out he’d go right back to trying to change the world—when I met him he was out of prison and fighting a giant dam that would have drowned the Peshawar Valley.”

“And his legend never really died, at least among the Pathans,” said Allie, who put another slide on the screen, this one of a great procession of people winding across a rugged mountain road. “When he died in 1988, at the age of 97, still under house arrest, 200,000 people came to his funeral. Tens of thousands of them marched for dozens of miles over the Khyber Pass. There was a five-day ceasefire in the Afghan Civil War.”

She paused, and Maria said: “Thank you all three of you. This is a remarkable story; I only knew it in bits and pieces, and Marco –Professor Vukovic—I had no idea you’d known him in person, though I should have guessed.”

“It was the only story I could think of when I saw those posters,” the old man said. “And after what happened today in Ahmedabad . . . .Well, the point is for me: anyone who says Islam is violent better be prepared to explain why it produced the greatest nonviolent army of all time. You could call him a jihadi, I guess, but he always said that ‘Islam is amal, yakeen, muhabat: service, faith and love.’ And it wasn’t just Khan. If you want to argue that religion gets in the way of progress, you better be able to explain Gandhi and his Hinduism, or King and his Christianity. I don’t believe in God, as I’ve said, but I do believe in history.”

“Unless there are questions, I think that’s enough for the morning,” said Maria. “We’re very very grateful to you Professor Vukovic, and also to your assistants.”

“I’ve got a question,” said Jukk, who looked annoyed. “For Allie. You’ve been telling us what a great guy this Khan is, but you’ve got a gun on you all the time. So what are you talking about?”

Professor Vukovic started to rise, his face coloring, but Allie but a hand on him. “Don’t worry, Professor, I’ve got this,” she said. She pulled up the cuff of her jeans so that everyone could see there was no longer a holster on her boot. “I got rid of the gun a few days ago,” she said. “And I’m not going to tell you all the reasons why. But I will tell you what I was reading when I finally made up my mind. It was a talk that Gandhi gave to the Pathans when he went for a visit.” She rummaged around for a moment in her notes, and then pulled out a piece of paper.

“Gandhi sat and talked with a bunch of Khudai Khitmatgars when he was visiting. And he told them they needed to be nonviolent in their hearts as well as their actions. He said that a true warrior would feel stronger without a rifle than with one. He said ‘a person who has known God will be incapable of harboring anger or fear within him, no matter how overpowering the cause for it may be.’ I’m not there yet—in fact I’m not anywhere near there yet, so don’t test me. But I’d like to be.”

Allie walked over to Yasmin, who was sitting in the front row, and took both her hands in hers and sat on the floor in front of her, and said: “I’m sorry about what happened to your poster. I think I may have been the cause of it, and I’m really really sorry. And I hope you’ll take me to a mosque someday, so I can see what it’s like.”

The hall emptied slowly, people talking quietly as they headed for class. Cass walked Professor Vukovic slowly back to his office; he was leaning more heavily on her arm than she ever remembered. She laid and laid him out on a small cot next to his desk, and loosened his tie—he was asleep in seconds.

Allie was the last person left in the auditorium, cleaning up the papers and shutting down the computer screen. Maria, who’d been lingering by the exit, came down the stairs to the front, and sat there watching her. After a minute she said:

“Two things. One, that was beautiful. One of the most important things that’s happened at this school ever. We could send this class of students home right now and most of the teaching would be done. Second, Professor Vukovic told me some of your story. I have some resources for you—some people to talk to when you’re ready. But are there ways I can help?”

Allie looked at her and said, “would you go to Mass with me someday?”

“I haven’t been to Mass for 20 years,” said Maria. “I would . . . love to. This weekend.”

***

“I think I like this one best,” said Gloria. “Definitely.”

“Caffeine Free Diet Coke?” said MK. “Literally this has nothing in it except chemicals. Nothing at all.”

“It has a gold can,” said Gloria.

“That’s a good point,” said MK.

They were standing at a table set up in the small private dining room. Usually it was used by yoga instructors planning the day’s classes (and escaping from over-eager students who wanted to talk about subtleties of the chakras), but today Maria had reserved it for a special occasion: a joint party for Gloria (6) and Professor Vukovic (95), whom Cass had figured out were birthday twins. It was a small affair: MK and Perry had flown in from San Francisco, and Maria had driven Gloria up from Colorado Springs—it was Saturday, and her mother had said it was fine to spend the night. She’d also given her blessing to the bonanza of Coke Cass had planned: they’d had a careful taste testing of every Coke product they could find, each poured into small plastic cups. Professor Vukovic had decided Coke Zero Cherry reminded him of the slivovitz plum brandy he’d grown up with in Serbia, Perry confessed a perverse affection for Diet Coke (“liquid sandpaper?”), and the women had all opted for Coke Classic in the red can.

“The red can is nice, but gold is best. Like the Olympics,” said Gloria.

“I’m going to be in the Olympics. In judo. Allie is going to teach me.”

“We’re going to learn together,” said Allie. “It seems like a good thing . . . to know.”

She hadn’t met Perry and MK till the night before, when she’d spent the night with them and with Cass, drinking beer in the aspen groves after the yoga students had retired for the evening. They’d hit it off easily, and eventually Allie had told a little of her story.

“Judo sounds smart,” said Perry. “Maybe I’ll take it up.”

“No need, sweetheart,” said MK. “I’ll take care of whoever comes after us. Your job is to cook.”

“I have been cooking, don’t worry,” said Perry, who had spent the previous week in their San Francisco apartment perfecting several Serbian dishes, especially cevapi, which was minced lamb, almost like a skinless sausage, served in a flatbread. He took the top off a serving dish, and handed the first to Professor Vukovic.

“Cevapi?” he said. “Which I haven’t had in—I think I was in my 60s the last time I had it.” He took a bite. “This is fantastic,” he said. “You’ve made an old man very happy.”

“It’s spicy,” said Gloria. “I don’t like spicy.”

“That’s why I’ve made you something very special,” said Perry, opening another dish. “Chicken fingers?”

“Do they have french fries?” she asked.

“Of course,” said MK. “Can you even have chicken fingers without French fries? I think it’s illegal.”

“Here’s what I want to know,” Professor Vukovic asked Gloria. “If we’re just eating the fingers, what happened to the rest of the chicken?”

“Oh,” she said. “They send the rest of it to KFC. They have, like, breasts and thighs.”

“That makes sense,” he said.

They ate and chatted, and eventually got around to the birthday cake, which had 101 candles. “I don’t think either of us quite have the breath,” said Professor Vukovic. “Maybe everyone could help blow them out?” They did, and toasted the birthdays with a glass of actual plum brandy (“this is a lot like Coke Zero Cherry, except not at all,” said Maria). And then they opened presents, mostly for Gloria: a tiny white gi for her to wear at judo, a stuffed penguin six inches taller than she was, and from Maria a Brownies uniform. “I think you’ll like Brownies, and I’ll make sure Cass or Allie or I are there to take you every week,” she said.

Gifts for the professor were somewhat harder. “What he’d really like are more documents about more uprisings,” Cass had told MK and Perry. But in her ongoing effort to clean out and digitize the files, she’d found a picture she thought she recognized. When she showed it to Allie, she agreed, and together they had it blown up and framed. When he unwrapped it, the professor paused for a long moment.

“1972,” he said. “In Kabul, where he was in exile at the time. I never met Gandhi, but meeting Khan was as good. Maybe better. Even then, even an old man, he—well.”

“We know exactly what you mean, Professor,” said Maria, her eyes bright. “Trust us, we know exactly what you mean.”

Within half an hour, Gloria was asleep in a corner of the room, wearing her Brownie sash over her judo robe, and clutching a gold can. Professor Kinnison—Mark—and his husband Tony had joined the party after getting their boys to bed, and Professors Lee, who gave her colleague a present she’d had smuggled out of China just for the occasion: a ticket to the Chinese lottery, with the nation’s red flag printed on the back. “I’m not sure what will happen if you win,” said Professor Lee. “It’s only officially open to Chinese nationals. But we’ll figure out something.”

And Linny came in too, ruddy from a day of free-climbing in Cheyenne Canyon, and Professor Ramakrishnan. When everyone had finished toasting the Professor with the brandy, and after Perry had played Robert Murphy’s 1969 classic “Happy Soul Birthday,” the professor cleared his throat and said:

“I’ve got something to say, something that only Maria knows about. It may take a bit of the celebration out of the air, but you people represent the family I have left, so you need to hear it. Some of you I’ve known for many years; Salgado, I’ve known you for two weeks. But I like and trust you all, and I’m going to need to your help.

First thing is: there won’t be a 96th birthday party. The doctor diagnosed me with pancreatic cancer in August, and pancreatic cancer is a bad one. I won’t be getting aggressive treatment: I’m 95, and that’s a long time, and I’m weak enough as it is.”

Cass started to weep, thinking of the times in the past weeks when the professor had run out of energy, gotten out of breath. She turned away.

“Goldfarb,” he said. “None of that. We’ve got almost all my papers digitized. My work lives in the cloud now, whatever the cloud is—it has a better memory than I do. And you’re perfectly capable of managing all that data; you’ll need to be the clearinghouse now.”

“Anyway,” he continued, with real enthusiasm, “this gives me a chance to actually implement an idea I’ve had for some years—a new technique, if you will. MK, Perry—as I understand it, the problem you’re facing is that the federal government has turned up the heat on your oil-train protests?”

“Wait,” said Linny. “You can’t just tell people you’re dying and then change the conversation to some new protest technique. I’m like a jock, but even I know that.”

Cass was sobbing now, and Tony too.

“Please stop it,” said the professor. “You have no idea how hard it is to be 95. When we were blowing out the candles, Gloria said to me ‘you’re too old,’ which is about the truth. But this particular idea actually has me wanting to live a bit longer, just to carry it out. It was the first thing I thought of when the doctor told me my diagnosis. So, help me: Khatoane, Alterson: the government is cracking down?”

“Yep,” said MK, who’d been weeping a bit herself, but who gathered herself quickly. “For a year our standard practice was blocking the tracks. It got publicity, and it helped remind people that there were train tracks running through their neighborhoods, which a lot of people didn’t even think about. But the Department of Justice has just declared that ‘interference with interstate commerce by rail’ will now be treated as a federal crime. What Cass spent a night in jail for might get you a decade in jail by this time next month—all over the country.”

“So. Perfect,” said the professor. “It seems to me that what you need are some people for whom a decade in jail doesn’t sound like much of a threat,” he said. “People like, say, me. I’ve been doing a little research. At any given moment, of 300 million Americans, about six million are living with a terminal diagnosis. Say half of them are confined to a hospital or their beds. That still leaves three million potential . . . criminals.”

“Um,” said Perry, “like old dying people out on the train tracks?”

“Precisely,” said the professor. “So we get arrested, and charged with something that gets us ten years in jail. By the time there’s even a trial we’re probably dead. And if we’re not, well, it will be an awfully good opportunity for a necessity defense. We’ll argue we had no choice, except to leave behind a disintegrating world.”

“That’s good,” said Tony. “And the thing is, lots of people, when they’re dying, they really are thinking about like their kids, their grandkids.”

“I know I am,” said Professor Vukovic. “I mean, I don’t have kids or grandkids, but I know young people all over the world. For the most part I’m an optimist—how could I be otherwise, when I know better than anyone what movements can do to change things. But global warming is one of two issues that make me very dark, because it has a time limit.”

“A time limit?” said Mark.

“A time limit,” said the Professor. “Dr. King always said—quoting the abolitionist minister Theodore Parker in the 1850s, I believe—‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.’ Even Obama said it, in his inaugural. It means, I think, ‘this may take a while, but we’re going to win.’ And true enough. I’ve watched, in my lifetime, women get the right to vote and black people the right to sit in a restaurant and gay people the right to get married. I watched you two get married,” he said to Mark and Tony, who stretched out a hand for each other and smiled. “We had slivovitz that night too.

“But in some basic way it didn’t matter how fast any of that happened. It mattered to the people who were suffering, of course, but not to the outcome; eventually justice would prevail. But these other two issues—well, think about global warming. It’s not even really politics. It’s basically just physics. Pour enough carbon into the air and the planet heats up. And past a certain point there’s not much you can do about it. One of the happiest images of my life was the first picture the astronauts sent back of the earth, our blue marble floating in black space. But you know what? The picture doesn’t look like that way any more. Most of the white up top is gone; the ice just keeps melting. Cass and I were on the skype machine last week with Inuit friends in Yellowknife—they have fire after fire now across the tundra. So it scares me.”

“And you’re going to do what exactly?” said Mark.

“I’m going to find—well, Alterson’s going to find, with his magic internet—a bunch of people like me with literally nothing to lose. And we’re going to sit on those railroad tracks, in all kinds of places. And when we do the reporters are going to cover it like crazy because it’s not what they expect. They expect young people to be idealists. They expect old people to be . . . being old.”

“I like it,” said Tony.

“I don’t like it,” said Allie. “Old people have earned a rest.”

“Old people have not earned a rest,” said Professor Vukovic. “Not us. We’re the first old people who are going to leave the world a worse place than we found it. We’ve been resting a good deal too much.”

“You haven’t been resting,” said Cass. “You work all day every day.”

“Well, I haven’t been to jail for a good long time,” he said. “I felt a little jealous when you went the other day. Though, frankly, I doubt I’ll make it there. It seems to me that even if I get arrested, the time it takes to mount a defense and go to court will probably stretch well past when I’m supposed to—you know. Anyway, this is the only item left on my bucket list.”

“The right domain name is crucial,” Perry said, typing furiously. Bucketlistbrigade.org. is available. Also .com and .net. I’m buying them all. My birthday present.”

“Excellent,” said the professor, who was beaming. “We can meet in the morning to figure out a recruitment plan.”

“I’ve got a question, though” said Mark. “You said there were two problems that left you feeling pessimistic. What’s the other one?”

“Oh,” said the professor, a little somber again. “Well, if climate change is physics, this one is biology. It worries me how close they’re getting to being able to genetically modify people, to make designer babies. All the live-forever stuff. All the singularity stuff the libertarians in Silicon Valley are always talking about.”

Cass thought with a start about her lunch with Matti, but the professor was still talking. “I’m not going to get the chance to do anything about that, though. I have an idea or two, but your generation will figure it out, or not. And I’m not going to live forever. In fact—I hate to break the party up, but I’m feeling nearly as tired as young Gloria. And since I now have something to live for, maybe I better get to bed.”

He drained his glass of brandy, and gave each of them a hug. Leaning on Cass, he started out the door towards his apartment, Allie trailing behind with the framed photo of Khan with his arm around the slight Serbian. MK picked up Gloria in her arms, handing the gold can to Perry, who followed them out in the hall. The professors stayed behind, cleaning up a little and talking quietly among themselves.

Sounds like Gus is putting in a plug for thirdact.org

Don’t miss the call Wed Jan 26 at 8 ET

https://thirdact.org/events/third-act-all-in-call-january-2022/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=7704efea-30bf-4bd0-9871-8ad311264ef1