It's Cars That Done It

One technology did more than any other to transform America and the earth

For the second time in my lifetime, we’re about to make a crucial political mistake as a nation based on high gas prices. In 1980, after the oil shocks and gas lines of the previous decade, we elected Ronald Reagan, ushering in forty years of a world where “government is the problem, not the solution”—and therefore ushering in ecological crisis, cartoonish inequality, and racial backsliding. And now, even as the January 6 hearings definitively uncover the rot at the core of the Republican party, we’re about to return them to control of Congress mostly because gas is five bucks a gallon.

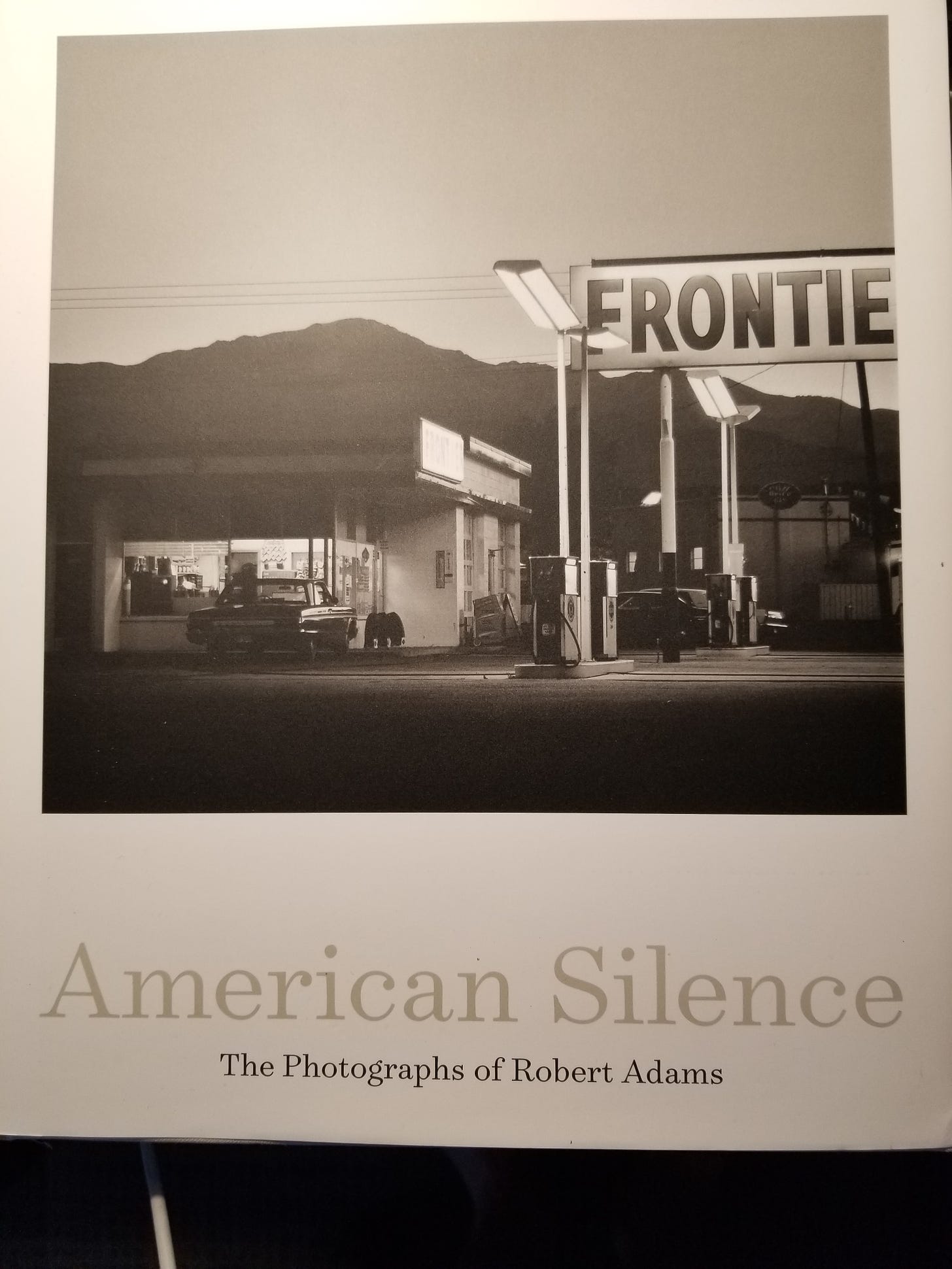

But that barely scratches the surface of the way that cars came to dominate—and distort and deform—American life, and with it the planet. I had the honor, earlier today, of giving a talk at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in conjunction with a massive show by the photographer Robert Adams, titled American Silence. It covers his work over more than half a century, documenting the stark beauty of the American West, the ordered human settlements that first marked it, and then the sprawling suburbs that gobbled it up. His most famous image (a gas station in front of Pikes Peak) is on the cover of the show’s catalog , and you can see a very low-fi version above thanks to the camera on my phone. But search out the show if you are in Washington, or the accompanying book, with a superb essay by Terry Tempest Williams.

The timeline of his life and work begs the question: how did this happen? Of all the forces unleashed in America, it seems to me that the rise of the automobile was most important. When World War II ended, there were less than 25 million cars on the road in this country; twenty years later that number was 118 million and rising fast, and in the meantime we’d built the interstate highway system. The car was the essential ingredient for the great American project in those postwar years: building bigger houses farther apart from each other. And that suburbanization rapidly changed who we were: from people linked to each other by the constraints of geography to people centrifugally flung from each other by the apparently liberating power of the private automobile. We went from people who traveled (together) by train and streetcar and boat between towns and cities that were relatively compact and contained, to people who…sprawled. Alone.

That liberation may have been more apparent than real. The average American has half as many close friends as the average American of the 1950s—because when you spread out, you run into each other less often. But even if they didn’t actually make us happier, we clung to our new forms tenaciously, and when they were threatened in the 1970s we lined up to save them. Listen to Jimmy Carter, futilely appealing to us to grow up: The energy crisis, he said, was a reminder that “ours is the most wasteful nation on Earth.” As the gas lines grew longer, his sobriety deepened. “All the legislation in the world can’t fix what is wrong with America,” he said. “Too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” he said, sounding different than any president had ever sounded. We should change — we should learn “that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning, that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.”

We preferred Reagan’s bland enchantments—and in the decades that followed we just kept pouring carbon into the air, with ever larger vehicles, until now, as the Washington Post reports this morning, “extreme weather is tormenting every region of the U.S.” even before summer officially kicks in. (Oh, and the “historic heatwave” afflicting Europe will “intensify into the weekend.”) America has put a quarter of all greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, a mark no other country (not even the vastly more populous China) will ever match. And it was that suburban spree that really did it—not factories, but cars and the huge distant homes they enabled.

Now, of course, we can begin to see a future where electric vehicles will at least slow the flow of co2, and render gas prices less politically potent. Those will be good things, and in the short-term perhaps the best we can hope for. But even a ton of Teslas can’t reverse the other impacts of this most fateful technology; that will require a change in our desires—in our personalities—towards something less private and more public.

In other climate and energy news this week:

+Europe is setting exciting new records for solar power production—at one point on Wednesday the sun was supplying 60% of Germany’s power

+Global climate talks drag endlessly on—at the moment, China is rejecting efforts to label it a “major emitter” under international treaties, even though it is a…major emitter

+Might drought shut down Old Faithful? It might.

+Three cheers for Fernanda, who trundled around her lava-ravaged Galapagos island till she met some scientists who confirmed she represented a species long thought to be extinct!

Our epic nonviolent yarn begins to approach its climax! If you want to read the first 74 chapters of The Other Cheek, you can find them in the archive.

Minister Hua reflected, not for the first time, that the job of state security usually involved dealing with one person at a time. There were eight billion people on earth, and he was the highest ranking intelligence officer for the country that contained twenty percent of them, and yet here he was studying the daily routine of a 24-year-old living in Silicon Valley. Matti Persson got up at 6:30 and went to a gym where he spent one hour and $65 for the privilege of riding on a stationary bicycle while a woman named Jessica McClure (27, resident of Richmond) yelled at him and a dozen others. He then waited in line for an average of eight minutes so he could pay $9 for a paper cup of green tea from a nearby shop (barista Todd Eintracht, 31, residence East Oakland) before driving to his office—and so on, a schedule he adhered to with a rigor that would make grabbing him almost comically easy, though after that the laughs would, he knew, soon cease.

He told his secretary to call General Youxia, and a moment later was talking to him through the speakerphone on the desk.

“General, I just wanted to make sure you were signed off on the Persson thing—yeah, the kid that Colonel Wang wants us to detain in California.”

“I understand he’s a weak link in Baby in the Moon,” the disembodied voice growled.

“True,” said Minister Hua. “I have no idea why he and his team were read into this thing in the first place—it was back at the beginning, when our researchers were trying to figure out which genetic researchers would make good . . . partners, long before the current plan evolved. But he knows most of it. So do his superiors at the Institute, but they don’t have his . . . connections.”

“He knows the DL, yes?”

“He visited with him in India two years ago, shortly after the walk began.”

“And he studied at the compound where the small girl in the robe was seen?”

“Briefly—and he is still in contact with its staff.”

“So what are we waiting for?”

“What we’re waiting for is . . . authorization, I guess. This is not how the game is normally played, not at all. We don’t go grab people on American soil.”

“Perhaps it would be simpler to eliminate him.”

“It would, but then we’d never figure out exactly what this whole crew is up to. And we don’t really do assassinations on foreign soil, at least American foreign soil, at least of people someone might notice.”

“These are special circumstances. President Xi is counting on everything going smoothly.”

“So, your authorization, general?”

“I think this falls . . . more under your jurisdiction, Minister.”

Hua sighed. He knew that this meant he was the fall guy if something went wrong, and a lot could go wrong operating halfway across the planet. But he also knew that for the moment General Youxia had more pull than he did. For the moment.

“Okay,” he said. “So let me ask you something else. I had the head of the Geological Survey in here this morning. The ice dam on the upper reaches of the Tsang Po is getting worse, not better.”

“I just saw the satellite pictures myself. That’s a lot of water backing up there.”

“If it goes, it’s going to wipe out a large corner of India.”

“Colonel Wang tells me it’s the corner where the DL is hanging out right now, so that would be one problem taken care of.”

Minister Hua stared at the phone, wondering if the General was really hoping for an ice-dam to come apart so that it might drown a political opponent a thousand miles away. Colonel Wang would obviously be in favor, but Colonel Wang was crazy. Surely her boss was . . . less crazy?

“General, if we don’t warn people downstream the death toll could be in the—the death toll could be very high.”

“Well, it won’t be our fault,” the General replied. “Everyone knows that global warming is melting the Himalayas, and that this is just the kind of thing that happens.”

“But a warning . . .”

“A warning would just get everyone worked up. We’re not going to go getting people mad at us, not when we’re on the edge of our biggest operation ever. Anyway we’ve got people boring a hole through the ice. President Xi will want to see us taking the initiative to solve the problem, not tell the world about it. Of course, if you’ve got objections, you can raise them with the Central Committee.”

“No need,” Minister Hua said, who knew his position was shaky enough already. “We will keep an eye on it. If we’re lucky the ice will wait till after the New Year to break. Good day, General.”

The general hung up without replying, and Minister Hua tapped out a quick memo on his computer. He barely hesitated before he hit send.

He felt as if events had taken control of him instead of the other way round. There were four days left in the year, and his main hope was to get through them.

Matti Persson sat in the locker room at DharmaWheel, pulling on his shorts and shirt which the gym laundry had cleaned for him; a morning raga tranced through the speakers, all sitar and tabla. He tied a bandana artfully around his brow, and then stepped out into studio, which was half-filled with other youngish people climbing aboard their bikes and starting to slowly pedal. Matti bowed to the instructor, Jessica, and said ‘good morning sensei.’ He had, as usual, the vague sense that ‘sensei’ didn’t fit with the otherwise Indian theme of his exercise facility, but that was part of the DharmaWheel way, and since he spent $65 a day he was fully invested in the experience. “Hello sannyasis,” the instructor said, calmly. “Today is another day in the cycle of our lives.”

“It’s pretty much exactly like the Dalai Lama,” Matti thought to himself; but then, remembering the heat and smell and dust of actual India, he thought “in fact, it’s a little better.” He and the others cranked slowly for a few minutes, as the music began to slowly rev up, the beats-per-minute climbing in an algorithmically optimized ascent. Soon they’d reached a cadence high enough to demand some concentration, and that’s when the instructor adjusted her headset mike and began to yell. “Up on your pedals,” she said. “It’s karma time. Did you drink too much at the Christmas dinner? Karma. Did you skip a session this week just because it’s the holidays? Karma.” All around the room students were climbing out of their saddles, pushing their gears a notch or two higher, and beginning to charge as fast as they could. “Karma, bitches,” the instructor was yelling now, over and over. “It’s payback time.” Matti was pushing hard now, sweat beginning to bead beneath the bandana, locked in his zone. “Karma, karma, karma, karma.”

After sixty seconds the music dropped back a little, and instructor Jessica stopped yelling and said in a soothing tone, “Nirvana time, bring it down. Nirvana for two minutes, 60 rpm, 60 rpm.” As he slowed Matti felt a finger poke him in the side—he didn’t glance over for a moment because he was in his zone, and had forgotten there were other people in the room, but after a second poke he glanced to his right and saw a young woman with a face as red as the paintjob on his Tesla. He stared at her for a second, and then another.

“Cass?” he finally said

“Matti,” she replied, between huffing breaths. “Good to see you again.”

“But—but you don’t live here,” he said.

“No, she said, “and I would not voluntarily have this loon scream at me every morning either.”

As she spoke the instructor started yelling again. “Up on your pedals,” she said. “Dance on those bikes. It’s karma time again.”

“I don’t think karma means what she thinks it means,” said Cass.

“It means when you have to pedal really fast,” said Matti.

“Well, then I guess she’s right,” said Cass, who was now going too hard to roll her eyes. She barely made it through the minute to the next nirvana zone and when she’d caught her breath a little she said, “aren’t you curious why I’m here?”

“Because you realized you wanted to be with me, I assume,” said Matti.

“Oh for—look, no time for this. I’m here because we need to get you out of here.”

“Out of here?” asked Matti, looking around the studio. “I’ve already paid my $65, and once the class is started you can’t, you know, switch it for another day or something.”

“Out of tech world here, Silicon whatever,” said Cass. “We’re pretty sure you’re in danger.”

“Danger?” said Matti. “Why would I be in danger?”

Right then the slack music turned taut again, and the instructor began yelling about karma, and Matti stood in his pedals. Cass just sat there, slowly turning her feet.

“You’re supposed to be going hard now,” Matti said.

“It doesn’t feel good—it hurts,” said Cass.

“Pain is the spring that melts the ice of habit,” said Matti.

“Where did you read that?”

“Austin said it, he’s the guy who sells the packages here.”

“Well, in that case you’re in luck, because I think there may be plenty of pain in your future,” said Cass.

The tempo dropped again, and Matti sat back down. “What do you mean pain?” he said.

“I mean that Professor Lee and Perry have hacked—”

“Perry, the long-haired autistic guy, the guy who’s working against genetic progress, the guy—”

“That guy,” said Cass. “Though if there was a contest between autism and narcissism, I know which one . . . oh, never mind. Perry and Professor Lee back at SGI have a pretty good idea of what the local Chinese intelligence officials are doing, and what they’re doing is getting ready to disappear you.”

“I work with the Chinese,” said Matti. “I’m one of their chief content architects.”

“Be that as it may,” said Cass, “there are three cars of their agents waiting outside to grab you before you get to the place where you drink the green tea.”

“How do you know I drink green tea? Have you been spying on me?

“We’ve been spying on the people who are spying on you, and they have a great deal more interest in your habits than I do, and—oh for heaven’s sake.”

The music had risen again, and Matti was back pushing hard. Maybe even a little harder than usual, to impress Cass, who he was actually very pleased to see next to him. She seemed less pleased, and by now she wasn’t pedaling at all, just sitting on her seat and staring at him. When the sixty seconds ended, she said

“The last intercept we were able to get had the license number of your car, the address of this studio, and the address of the warehouse where they’re planning to take you for interrogation.”

“Interrogation?” said Matti. “Why wouldn’t the Chinese just call me up? We Facetime every day.”

“You do get that ‘the Chinese’ are not just one person?” said Cass. “These particular Chinese are looking forward to talking with you too, but I don’t think it will be a fun conversation.”

She pulled out her phone and passed it over to Matti, who began to study the screenshot of a computer screen with translated orders for his kidnapping. Meanwhile, the instructor approached the pair. “Is there a problem?” she said.

“No, sensei,” mumbled Matti.

“Maybe,” said Cass. “If this is an Indian-themed exercise class, why are you having everyone call you by a Japanese honorific?”

“Why are you not pedaling?” the woman asked.

“Injury,” said Cass. “Plantar fascism.”

“Oh,” said the instructor. “Well, don’t bother the other clients. We need everyone in a morning headspace. And injuries are the result of past actions, you know.”

“Injuries are the result of many things,” said Cass with a slightly threatening look.

“It’s okay, sensei,” said Matti. “We have to leave early anyway.” He unclipped his special shoes and climbed down from the bike. “You do have a . . . way out?” he asked Cass, as they walked from the room.

“I do,” said Cass. “And it’s not back through your locker room, because they have a man in there already. We’re going in here instead,” she said, pushing open the door into the women’s lockers. It was mostly empty, but a few of the occupants looked up and began to protest.

“Ladies, ladies—what year is this? 2014?” said Cass. “We’re all going to have one big locker room soon anyway.”

“He’s a cutie,” one of the women said. “Look at those pecs.”

“He’ll be back in a few weeks,” Cass said. “Fair game.”

Matti was staring straight ahead and blushing, and Cass kept one hand on his elbow, ushering him towards an emergency exit past the showers.

“It says ‘alarm will sound,’” he said, pointing to the door.

“Indeed it does, but Perry used his special autism skills to make sure it won’t make a peep. At least, let’s hope he did.” She pushed on the bar across the door and it opened without a fuss, spilling them out in a sunlit alley.

There, waiting next to two dumpsters, were Perry and MK, each one of them holding the handlebars of a pair of rental scooters painted lime green.

“Hey Matti,” said Perry. “Long time no see. You know how to use one of these things? They’re kind of fun.”

“Shouldn’t we take my Tesla,” said Matti. “It’s just around the corner, and it’s very fast.”

“And it has a pair of Chinese tracking devices on it,” said MK. “We just watched them put them on the back bumper.”

“Nice shirt,” said Perry, looking at Matti’s gunmetal gray t-shirt

“You think so?” said Matti. “It’s from RYU, Respect Your Universe. They’re like—wear them at the gym, wear them at the office. Not, like, the same day obviously, but—”

“Wardrobe time later, boys,” said MK. “I think we better get ready to leave, because I have a feeling they noticed you getting off your bicycles.”

At that moment a car closed off one end of the alley, and men began to climb out the front and back doors. Perry turned the handlebars of one scooter toward Matti. “Kick and step on,” he said. “Then the throttle is right here on the handlebar.” Matti tried, almost tripping on the cleats in the front of his bike shoes. But he wobbled off behind the other three, in a line headed down the other end of the alley. They turned the corner left onto a sidewalk, and heard a shout coming from behind them, and then the slam of a door and the squeal of brakes as a car launched into a turn.

“How fast does this go?” Matti said.

“14.8 miles per hour,” Perry said. “Because the speed limit in most cities is 15, and they don’t want people breaking the law and getting them in trouble.”

“Okay,” said Matti. “But these guys are in cars and they’re going to catch up to us pretty fast.”

“Terrain is our friend,” said MK, who was in the lead. She swung her scooter off Camino Real, and onto a footpath past a sign that said “Main Quad.” “I actually got into Stanford,” she said. “I guess now’s the right moment for a campus tour.”

They heard a car turn onto the footpath behind them, and when Cass looked back she could see the sedan racing after them, its tires tearing up the ground on both sides of graveled walk. “Um, they seem to not get the whole ‘footpath’ thing,” she yelled.

“It’s okay,” said MK. They flashed past a set of bollards set firmly in the ground, along with a sign explaining that the core campus was a “designated pedestrian area, part of Stanford’s contribution to fighting the climate crisis.” The car screeched to a halt just short of the pylons, and they could hear doors opening and men climbing out.

“How fast can people run?” MK asked. “Just curious.”

“I looked that up,” said Perry. “Assuming they’re not Olympic athletes, about 16 miles an hour—but that’s only over short distances. I think we should be just about okay.” The four, nearly abreast on their scooters, flashed past another pair of bollards and onto a paved walkway crowded with students. They went another hundred yards before MK said, “over here,” and stepped off her mount, leaving it next to the steps to a building marked Tresidder Memorial Union. They stepped inside, and saw hundreds—maybe thousands—of people their age milling around between fast food restaurants. “This way,” MK repeated. “Keep your back to the door, and your heads down.” They quickly occupied a table just outside Panda Express, the view to the door blocked by the counter full of napkins and chopsticks. But they were close enough that a few seconds later they could hear a man shouting at the security guard stationed by the door.

“Four kids just came in here,” the man said. “Where are they?”

“Four thousand kids come in here every lunch hour,” the guard said. “It’s Christmas week, but that’s when we have gifted-and-talented high schoolers from around the state for special seminars. It’s nothing but kids—how am I supposed to find yours?”

“He left,” said Perry, popping up for a look a moment later. “But I imagine they have people at all the doors now. I think we should go pretty quickly, which is a shame because the orange chicken at Panda Express is really quite good, especially considering the price.”

“Go where?” said Matti. “You just said all the doors are guarded.”

“Well, sure,” said Perry. “But there’s a computer lab in the basement, and we start there.” He guided them quickly down a set of stairs, and into a room filled with high-end workstations. At one end of the room a young man was waving at them. He wore a t-shirt that said “I Failed the Turing Test,” and he gave Perry a hug.

“This is Yang, everybody,” said Perry. “He got fired with me from Mothra.”

“Fired?” he said. “I got voluntarily severed. And with enough money to launch my new app. You saved me, man.”

“The food app?” said Perry.

“Yeah,” he said, turning to the others and lifting his shirt to show a small pod attached to his skin. “It monitors your blood levels continually, and when your sugar drops below a certain point it automatically orders a delivery from Chipotle. From anywhere you program it to mostly, but Chipotle is the default.”

“That’s cool,” said Matti. “Do you have second-round financing for that?”

“Um, maybe later?” said Cass. “Maybe we should get out of here first?”

“Right,” said the young man, calling up some pictures on his screen.

“So, you want to go to the parking lot by the football stadium, am I right?”

“Correct,” said Perry. “And it’s kind of a hurry.”

“How much do you weigh?” the young man asked.

“145 pounds,” said Matti.

“Less than that,” said Cass.

“More than that,” said Perry.

“None of your business,” said MK. “But about that.”

“Good,” said Yang. “These drones have been tested up to 350 pounds, but by testing I mean basically we lifted a freshman into the halftime show during the Cal game.”

“Drones?” said Matti.

“Air seemed the best bet for escaping,” said MK.

“And Yang is vice-president of the Stanford Autonomous Aerial Vehicle Club,” said Perry.

“Past vice-president,” said Yang. “GutCheck takes up almost all my time now.”

“GutCheck is a good name,” said Matti.

“Anyway,” said Cass. “We figured there wasn’t much other choice. We’ve got to put some distance on those guys—it will take them a while to figure out where we’ve gone. Maybe long enough that we can get away.”

“Also, it’s great proof of concept,” said Yang. “This will be pretty close to a new manned drone record I think. Peopled drone, I mean,” he said, looking at Cass and MK.

“Do we need to steer?” said Cass.

“Leave the driving to me,” said Yang. “It’s easiest from my computer down here, because I have my trusty joystick—but I think that it might make more sense to control you by phone from the roof, so I can see where you’re going. The directions are programmed in already—it’s essentially autonomous. And there are video sensors mounted on both units, so I’ll be able to see when it comes time to land. Just let me know if you see any, like, telephone wires or like, another drone, or anything.”

“To the roof,” said Cass, who was worried Matti might lose his nerve if given even a moment to consider. Actually, she thought, she was at least as worried she might lose hers. They all piled into an elevator, and when it reached the top floor they filed out, and into a short staircase that carried them on to the roof. Two large black machines sat in the middle of the flat expanse, and Yang wasted no time strapping Cass and Matti into harnesses and handing them helmets—they were kneeling on the roof, with the housing for the drones on their backs. “You’ll be able to talk to each other through the headsets,” he said. “And me if you need to—just press this button on the chin mic if you want to patch me in. These are quadcopters—four rotors on each—and I figure that if the building is being watched it might be best to lift you straight up, so maybe you’re at altitude before anyone spots you.” He pulled his cellphone out of his pocket, hit a few buttons, and the rotors began to whir.

“Okay, you guys grab on,” Yang said to MK and Perry. They looked at each other for a second, and then MK wrapped her arms around Cass’s waist, and Perry did the same with Matti.

“It should only take about 45 seconds,” Yang said.

MK flashed a thumbs up, and then the rotors began to lift, jerking them up in their harnesses like marionettes. Clearly, though, the machines were struggling with the weight. They could barely lift them off the ground—indeed Perry’s toes were still brushing the roof when Yang pushed another button and the drones surged forward toward the edge. As they passed over the cornice, now dangling above open air, the drone holding the two boys sagged again, dropping perhaps forty feet toward the ground. As Perry looked down, he could see two of the men who’d been chasing them—they were pointing and shouting into phones.

The drone kept sagging, but it kept charging forward too, keeping up with the girls who were fifty feet higher. They were speeding across the campus, and clearly Yang had them on a monitor, because they were whipping around trees and avoiding buildings by a few feet, like characters in a video game. As they came across the college practice fields at what felt like 70 miles an hour, the ultimate frisbee team looked up and began to wave. One winged a disc out in front, leading MK perfectly—when she took one hand off Cass’s waist to make the catch they erupted in cheers.

“It’s like quidditch for real,” said Cass into her headset.

“Quidditch?” said Matti into his headset. “Oh, yeah, from that book. Look, we need to be clear about something. Just because you came and got me, for what reason I’m still not sure, does not necessarily mean I’m going to be your boyfriend again.”

Cass, whose drone had begun to slow and drop toward the parking lot, just looked across at him and slowly shook her head. As they landed, Perry pointed back across the lot, where a group of four men could just be seen, running hard in their direction. He unhitched the harnesses and pushed Cass and Matti into a minivan, which was moving even before the door closed. MK looked around at them from behind the wheel. “Time to head towards home base, I think,” she said.

"We" didn't prefer Reagan to Carter -- some of us did, okay, but many of us did not. Some of us even took the warnings of the 70s and postponed driving for another two or three decades. I really have a hard time with this great American "we" that so often does not speak for so many of us, even sometimes for most of us (for example, "we" did NOT elect Donald Trump -- the non-representative electoral college did).

Thank you for a great and eloquent (and sad) newsletter today, Bill! 2 More 'car facts' for your readers: 1- An early (1960-ies) design + patent for an electric car was bought by a large car maker - just so they could lock it away + not threaten their business.

2- Train tracks were ripped out + used for highways, so that commuters had no choice but to travel by car. (Yes, I do not have all the names ready - search + you will find it)