Maybe we should have called this planet 'Ocean'

Because then we'd be paying more attention to some truly freaky data

Something very troubling is happening on and under the 70 percent of the planet’s surface covered by salt water. We pay far more attention to the air temperature, because we can feel it (and there’s lots to pay attention to, with record temps across Asia, Canada and the Pacific Northwest) but the truly scary numbers from this spring are showing up in the ocean.

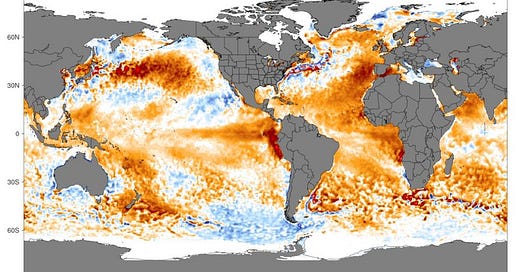

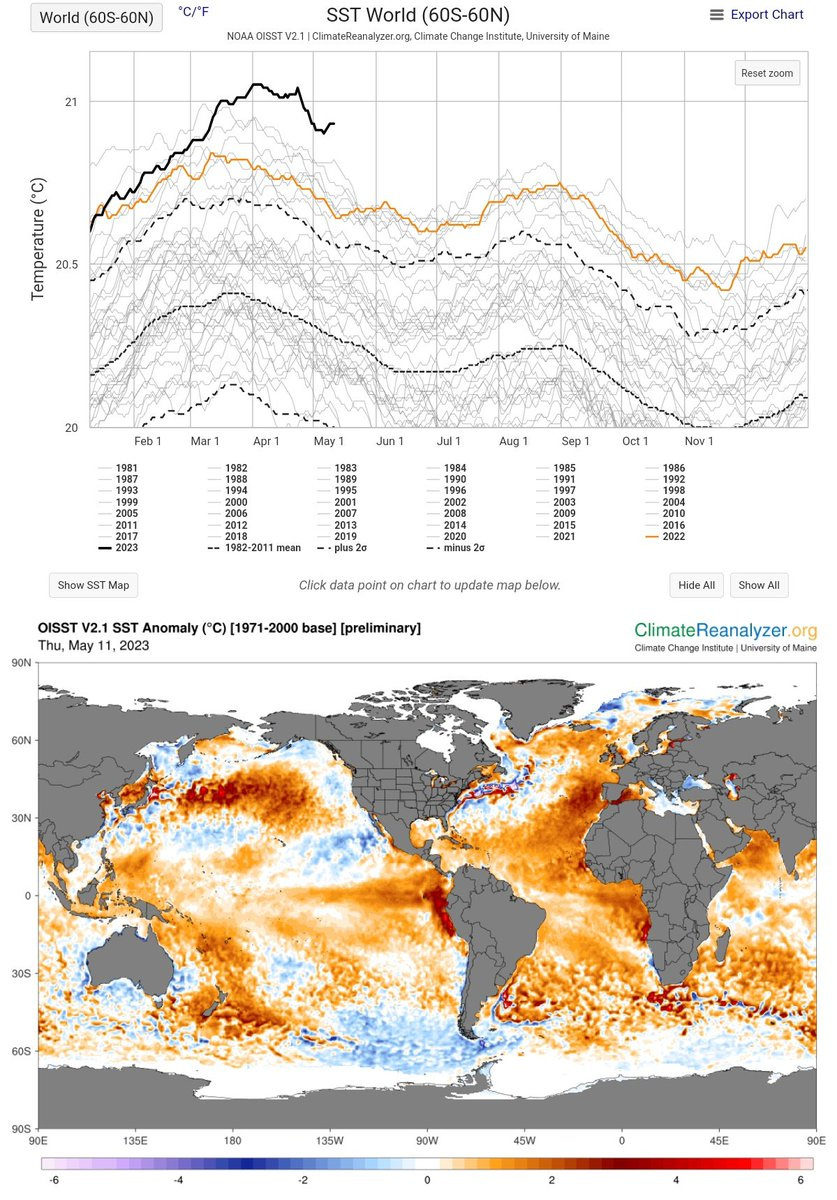

If you look at the top chart above, you can see “anomaly” defined. That’s the averaged surface temperature of the earth’s oceans, and beginning in mid-March it was suddenly very much hotter than we’ve measured before. In big datasets for big phenomena, change should be small—that’s how statistics work, and that’s why the rest of the graph looks like a plate of spaghetti. That big wide open gap up there between 2023 and the next hottest year (2016) is the kind of thing that freaks scientists out because they’re not quite sure what it means. Except trouble.

The magnitude of this jump has scientists somewhat perplexed and considerably more frightened—as the BBC pointed out, the numbers are extreme.

In March, sea surface temperatures off the east coast of North America were as much as 13.8C higher than the 1981-2011 average.

"It's not yet well established, why such a rapid change, and such a huge change is happening," said Karina Von Schuckmann, the lead author of the new study and an oceanographer at the research group Mercator Ocean International.

One factor at play is that seagoing vessels have been rapidly phasing out their use of “bunker fuel,” the literal bottom-of-the-barrel tarry sludge that ships have generally burned because it is very very cheap and because they are…out at sea. Research indicated that the pollution from this stuff was blowing back to port and damaging humans, so as Ryan Cooper reports it is being replaced with cleaner fuel. Big enviro win, except that the aerosols in the choking exhaust of those ships (the stuff coming out the smoke stack) helped seed clouds as it trailed out across the main shipping routes; the air is now clearer on those routes, and hence more sunlight gets through to the ocean.

But in a deeper sense, the oceans just seem to be heating very very fast now. A little-noticed recent study headed by Katrina von Schuckmann found that “over the past 15 years, the Earth has accumulated almost as much heat as it did in the previous 45 years,” and that 89 percent of that heat has ended up in the seas. That would be terrifying on its own, but coming right now it’s even scarier. That’s because, after six years dipping in and out of La Nina cooling cycles, the earth seems about to enter a strong El Nino phase, with hot water in the Pacific. El Nino heat on top of already record warm oceans will equal—well, havoc, but of exactly what variety can’t be predicted.

And the ‘can’t be predicted’ part is the real problem. Remember, people, this is an experiment we haven’t run before, and the test tube we’re using is the whole planet. Lots of things will happen: maybe the Beaufort Gyre will release a whole lot of freshwater into the north Atlantic, further disrupting the already weakened Gulf Stream. I bet you hadn’t been worrying about the Beaufort gyre, but a new study last week… Or maybe there will be more of the Midwest drought currently forcing farmers to abandon wheat crops at a record rate. Or ocean oxygen levels will keep falling, putting pressure on lots of species (except jellyfish).

Some things we can say with near certainty: the World Meteorological Organization predicted today that there was a 98 percent chance that sometime during this El Nino run the world will set a new annual temperature record. (I’ve been guessing 2024, but the odds that 2023 might break the alltime record set in 2016 are rising by the day and are currenty about one in four). There’s a very good chance, in fact, that at least for a year we will go past the 1.5 Celsius level that Paris set as the mark we should move heaven and earth to avoid. We haven’t moved heaven and earth—we budged Joe Manchin very slightly, though he’s now pushing back—and so we didn’t avoid it. Now what?

Now we have to organize as never before. This havoc, whatever form it takes, will produce pressure on our political and economic systems to do something. The oil industry will be trying to make sure that pressure is converted into yet more public dollars for carbon capture so they can go on burning coal and gas (check out this excellent summary of this particular scam from Food and Water Watch, and this NPR report on what happens when carbon pipelines rupture and suck out all the air).

So the rest of us better be prepared to give one last vigorous push to the clean energy project. As prices for the silicon in solar panels keeps falling, the convergence of political pressure and economic opportunity offers the world one last good chance of—not stopping global warming, too late for that. A new National Renewable Energy Lab study underlines the fact that this is our cheapest, fastest option; a new Nature Conservancy study shows it will take even less land than we used to fear. But maybe stopping it short of cutting civilizations off at the knees. That’s what we’re playing for, and this stretch of hot weather is going to be our last best chance.

In other climate and energy news:

+Princeton professors are joining the fight to get pension giant TIAA to divest from fossil fuels

In the short term, all of us who participate in the University’s retirement plan must be given a choice on whether to invest in climate destruction. Many funds with A grades on climate are available outside TIAA, although careful vetting is needed to avoid greenwashing, when companies present themselves as doing good for the environment when they aren’t. We urge the administration, faculty, and staff to work together to make sustainability the default and to offer a broad set of such funds to employees. In the context of today's climate crisis, the University's responsibility to its students must include striving to safeguard their future and standing with them as they fight for a livable planet.

And a good reminder that even if your pension plan is free of fossil fuel stocks, it may be chock-a-block with fossil fuel bonds

+Meanwhile, speaking of Princeton professors, a fascinating essay from art historian Karl Kusserow reflecting on a 19th century painting of a cholera outbreak and the climate crisis of today.

+Orcas may need King Salmon more than you do

+Asia is getting so outrageously hot—the Economist asks whether the remarkable street life of cities like Kolkata can survive. It describes the life of one coconut-seller plying his trade by bike:

The heat index – what the temperature “feels like” in the shade when air temperature is considered alongside humidity – hit 48°C soon after sunrise. To make it through the day, Mondal has bought orange-flavoured rehydration salts and mixed them into five bottles of water that he has stuck into a corner of his cart.

+The outlook is improving for recycling solar panels and windmill blades, according to CNBC

Solarcycle is a prime example of the companies looking to solve this climate tech waste problem of the future. Launched last year in Oakland, California, it has since constructed a recycling facility in Odessa, Texas, where it extracts 95% of the materials from end-of-life solar panels and reintroduces them into the supply chain. It sells recovered silver and copper on commodity markets and glass, silicon and aluminum to panel manufacturers and solar farm operators.

Thank god for truth-tellers like you, Bill. The news is awful but your grasp and the heart you put into it are keeping us going - thank you so much.

As you probably know, Michael Mann posted the same "NOAA SST World (60S-60N)" chart recently. That chart does not reveal the truly frightening trend of ocean heat over the past 6 decades. Dr. Mann and two groups of scientists co-authored a paper with a "Global ocean heat content in the upper 2000 m" chart that clearly shows the 60-year ocean temperature trend in *2020* [1920 typo corrected] (https://bit.ly/Springer27Jan20) and again this year (https://bit.ly/Springer11Jan23). The charts shows ocean heat increasing at a rate four times greater since the 1990s as compared to the previous 30 years.

Another paper published last August (https://bit.ly/AGU29Aug21) concluded that "Earthshine" as measured on the dark side of the moon has decreased about 25% from 1998 to 2017. It is a complicated calculation, and I was initially told by one of my mentors that 25% is incorrect, but later he took that back and confirmed it is. indeed, a 25% reduction. The point is, as you allude over and over, things are disintegrating abruptly right under our noses.

Who would have thought Jim Hansens "Faustian Bargain" would become kitchen table conversation?

What we are observing is evidence that—to use a currently poignantly sad analogy—Mother Earth is lying on the ground in a puddle of blood—having been shot in the thigh—and her femoral artery is bleeding out. We should, metaphorically, be applying a tourniquet, but we are debating, metaphorically, whether guns or troubled teenage boys are the problem. In climate jargon, we need to apply immediate short term measures to strategically cool specific "hot spots" that will do the most good in the near term while we ramp up the long term remedies.

James Hansen et al. also published a pre-print (for peer review) "Global warming in the pipeline" as you most likely know. The ABSTRACT begins with the astonishing findings:

"Improved knowledge of glacial-to-interglacial global temperature change implies that fast-feedback equilibrium climate sensitivity is at least ~4°C for doubled CO2 (2×CO2).... Global warming in the pipeline is greater than prior estimates. Eventual global warming due to today’s GHG forcing alone – after slow feedbacks operate – is about 10°C."

In simples terms (for readers), even if we were to cease carbon emissions immediately (2022 in the Hansen's analysis) the global temperature trajectory would continue upward and level off at around 10°C in a few centuries—passing through 6.7°C in one hundred years (~2125) unless we employ some sort of albedo enhancement and carbon removal.

Whether or not peer review gives a nod or refutes Hansen's paper, I believe it is time to seriously look at all options (ordinary and extraordinary) adhering to scientific method rather than speculation and gut feelings. That includes all forms of cooling the ocean, atmosphere, particular regions, seasons, natural, bio-mimicry and technological, benign and potentially dangerous and search for yet unknown means of cooling. We will soon have to decide what to deploy and at what scale. We need research to know the acceptable limits.